Going On Looks Alone

Brief job task simulations are often not particularly effective for evaluating an individual’s ability to perform a job that has a significant extended energy expenditure requirement.

- By Jim Briggs

- Sep 02, 2015

If you are hiring based on how someone looks, you may be discriminating.

Obviously, no professional would hire someone just because of the way they looked unless they were hiring models or actors. Do you look at the application to decide whom to interview? Sure you do. In doing so, you are creating a mental image of what that person has to offer. When beginning the interview process, you take note of a person's "appearance" and "business demeanor" relative to the job they are seeking. Obviously, a customer service representative will need a certain amount of politeness combined with the ability to steer the conversation to a satisfactory outcome for both you and your customer. This may be as much an art as a skill.

Relative to the subject of this article, Abercrombie & Fitch has had two decisions go against it in the courts. The company decided it wanted to project a "certain" image in its stores, but in 2005, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California granted a $50 million settlement to Latin American, African American, Asian American and female applicants and employees who charged the company with discrimination. The latest widely publicized case resulted in a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court regarding the hijab (Muslim head scarf) worn by a female applicant during an interview, which resulted in the retailer not hiring her. This is not an article about Abercrombie & Fitch, but I use their cases to bring to light a longstanding bias when hiring, which is, either they do or do not look like the person you may want for a particular job.

You wouldn't necessarily hire the customer service applicant to perform the jobs that are physical in nature and require strength, endurance, and agility, just because he or she demonstrated the skill set to be a good customer service representative. Or would you? After all, the person already has proven himself. But are you putting him at risk or are you refusing to move him because you don't think he can perform jobs that require strength, endurance, and agility because he doesn't look the part?

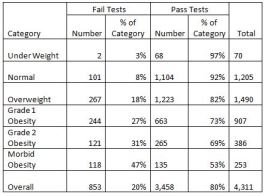

The study below represents 4,311 applicants for jobs that would be considered in general terms to be heavy physical demand. You can see a direct correlation between pass/fail rates and BMI, but BMI is not an appropriate indicator as to a person's ability to perform the work. This is obvious due to the number in the overweight to morbid obesity categories that demonstrated, during a job-specific physical ability test, that they can indeed perform the essential physical demands of the job.

The courts may be right by taking away the discretion of the employer to hire based on appearance. As shown in the chart above, roughly one-third of the qualified applicants (Grade 1, 2, and morbid obese) who demonstrated they could perform the work may not have been hired due to their unfit appearance. Also, notice that the underweight performers performed at a very high pass-to-fail ratio, with only two out of 70 failing the test.

So are you going to read this article and say that you have never hired one person over another because one was a better fit "physically" than another?

In reality, many factors go into the risk assessment. Have the applicants already conditioned to your job because they were performing similar work for another employer? Are they at higher risk for injury because of the work they performed for another employer? So what can we do to minimize the risk?

A properly validated job-specific physical ability test is an objective way to determine whether a person has the physical capability to perform the physical demands of the job regardless of appearance, age, or sex.

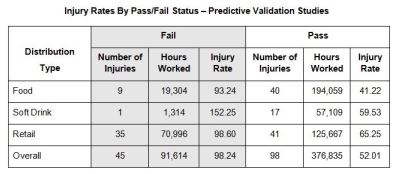

The table below represents "Injuries per hours worked" of employees who passed the test versus employees who failed the test (Anderson and Briggs, 2008). To arrive at the data in the table below, 549 employees were tested in three distribution areas: food, soft drink, and retail. All of the applicants were tested for strength and endurance. For purposes of the study, all of the applicants were employed regardless of passing or failing the physical ability test. These employees were tracked over their period of employment up to two years.

As you can see in the table, the injury rates for those deemed to fail the test were much higher than for those who passed the test.

This leaves us at a fork in the road. Do we guess whether or not a person is physically capable of performing a job, or do we test him? Statistically speaking, it makes sense to use a physical ability test, but not all tests are created equal and not all jobs warrant a physical ability test.

ADA Requirements

The ADA, as ruled in Indergard v. Georgia Pacific Corp., requires a test to be given post offer if it meets any one of the seven criteria below (EEOC interpretative guidelines, http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/guidance-inquiries.html).

1. The test is administered by a health care professional.

2. The test is interpreted by a health care professional.

3. The test is designed to reveal an impairment of physical or mental health.

4. The test is invasive (such as involving measurement of blood pressure or heart rate).

5. The test measures an employee's performance of a task or measures his/her physiological response to performing the task.

6. The test normally is given in a medical setting.

7. Medical equipment is used.

The EEOC's guidelines state that just one of items above may be enough to determine that a test or procedure is a medical exam, and therefore needs to be given post-offer.

Post-offer physical ability tests that are considered medical tests for new hires and return to work are both legal and effective for employment selection decisions, so long as the tests are job specific. Be careful, though, not to turn an agility test into a medical examination or use a test as part of a medical exam if it is not job specific.

Agility tests or work simulation tests monitor an employee's ability to perform a job's essential physical requirements, such as lifting or other "job task simulations." But do you really want to administer an agility test? Several issues can arise with this type of test.

First, is there consistency in test administration? In other words, is every test given in the same manner and scored the same at each location by each test administrator? Health professionals are trained to administer tests in an objective and reliable manner. If the health professional is external to the organization, there is even less potential for bias in test administration and scoring.

Second, when administering a pre-offer agility test or job task simulation, the test administrator cannot ask any medical history questions and cannot take physiological measurements such as heart rate or blood pressure in order to ensure it is safe for this person to take the test. Without such information, the test administrator is "flying blind." Who do you think is liable if a person is injured as a result of your test? Such questions and measurements would deem the test to be a "medical test," though, which would mean it would need to be given post-offer.

Third, you can only observe "job task simulations," such as lifting or walking, etc. Performing these tasks without benefit of taking heart rate or other physiologic information only tells the test administrator whether the person can perform that task one time, not whether the person can perform the task multiple times over an extended period.

In other words, brief job task simulations are often not particularly effective for evaluating an individual's ability to perform a job that has a significant extended energy expenditure requirement. Thus, such tests would not necessarily identify an individual who would not be able to repeatedly perform essential job demands over the course of a shift.

To test for endurance, there would need to be quantification of the requirement of that specific job, and the test would provide an objective assessment of the individual’s ability to sustain the measured requirement over the course of the shift.

So here we are at the crossroads. Do we go on looks alone? Do we use a less effective agility test? Or do you use a validated post-offer physical ability test for the best ROI? The decision is yours.