Vision 20/20: Preventing Opportunity Blindness

We humans are great at connecting dots when information is missing. The downfall of that is it leads to inaccurate assumptions, which lead to consequential actions, which lead us toward unplanned and often unwanted results.

High-performing teams redefine excellence at the point where realization and achievement intersect. It is at this juncture where opportunity is at its peak and readily accessible for those who can see it and diligently work hard to make it their own.

Maybe today? Maybe tomorrow? Perhaps the next day? Opportunities. Will they come or will they go? So often these questions are asked, but so infrequently are they answered. Yet for some seemingly lucky people, opportunities seem to be there, always present and never-ending. Why? How is it possible for one colleague to be endowed by the grace of fortune while another ponders aimlessly in obscurity? Why is it that one is invited to the important meetings while the other awaits an abbreviated out-brief? This reveals the biggest of all questions: why have you perhaps not advanced to the point of impact where realization and achievement intersect?

Most likely, the answer to these questions is sequestered within the confines of your vision or blindness and the interrelationship between each as they interact in delicate balance that produces outcomes and results; expected and unexpected.

It's my experience that most occupational safety and health professionals go through their careers waiting for the chance to take advantage of opportunities when they arise or simply hoping they do. I have seen many work very hard in directions that placed them in undesired positions or in positions that did not offer intellectual growth and professional development. I have seen early career professionals squander away amazing opportunities simply because they either did not see them or did not realize the potential of these prospects.

"Vision 20/20 - Preventing Opportunity Blindness" is designed to help you recognize the filters you have in place that are keeping opportunities at bay and to show you how to identify opportunities by being mindful of the power of assumptions, by applying process thinking principles and by understanding how human nature actually helps us in the decision-making process. The goal is to offer an alternative way of looking at challenges and to help you and your employer innovate past the competition.

Together, we will focus on the power and decisional influence of assumptions and how they can be helpful and harmful to your career and your organization. We will explore the inner relationship of vision and blindness and address how they are powerfully interlinked. We will uncover the major difference between innovative and non-innovative people and how their mindset can drive both by design. We will unveil a true story that demonstrates the power of vision despite all odds and how financial success can come from it. We will touch upon process thinking and how it can be used to positively change outcomes for good. You may even discover a new way to view and conduct your incident investigation process along the way. We will dive right into how and why we, as humans, make decisions and how to leverage this phenomenon to open our apertures so we can have a wider, deeper perspective of the business world around us. We will provide a road toward excellence, a map if you will, to help you start the process of thinking differently.

Our goal is to offer you the opportunity to think differently about how to not only identify, but to also create amazing opportunities for yourself and your employer.

What we are about to discover is how you can prevent opportunity blindness through the power of knowledge and strategy.

Opportunity Hidden In Plain Sight Through the Influence of Assumptions

One of my favorite quotes on this topic is the one from Thomas Jefferson, who reportedly proclaimed that, "Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work." This is a powerful statement because most people do look for the easy way to reach their aspirations when in fact there rarely is an easy way. Some spend their days gaming the system all the meanwhile using the same energy required as it takes to focus on actually achieving greatness, something special.

Let's take a different spin on this quote and say that opportunity is missed by most people because it is hiding in plain sight. Opportunity is missed because we dismiss it as irrelevant by the way we think and by how we choose to see the world around us. I see this phenomenon materialize every hour of every working day.

Consider statistics for a moment. Visualize that I have a quarter in my hands. If I were to flip this coin, what are the odds of getting heads or tails? I have been in a room full of over three hundred attendees where I flipped this same coin and most if not all agreed that if we simply apply the statistical formula, the probability of heads or tails equals the number of successful outcomes divided by the number of possible outcomes. Most people agreed the odds of one or the other materializing is fifty-fifty. About half the room raised their hands for heads and the rest raised their hands for tails. Very few were not certain and abstained from the vote.

So let’s try this virtually. I am going to flip the coin now. When I do, say heads or tails out load. Ready? Here goes. The coin is flipped, caught, and is sandwiched between my hands.

Alright, what did you choose? Heads or tails?

Taking one hand away, the coin turned up heads so the likelihood is high that some of you predicted correctly.

I will flip the coin in the air again. As before, say heads or tails. Ready? Here goes. The coin is flipped, caught, and is sandwiched between my hands.

All right now, what was your selection this time? Was there a change from your first choice, or did you stick with it? The coin turned up heads, so some of you correctly predicted this outcome once again. Some of you likely selected the wrong one, but that is okay; it is statistics, right? Fifty-fifty?

One last flip. Say it out loud, heads or tails? Here goes. All right. Did you stick with selecting the outcome of the first and second flip, or did you change based on the seemingly lower odds of coming up heads a third time?

Removing one hand, I see that it turned up heads again. As a matter of fact, the coin will turn up heads every time because the number of successful outcomes equals the number of possible outcomes on a two-headed quarter. The probability is equal to one and not fifty-fifty.

So what happened in that room of three hundred? What happened just now? Why did some of you undoubtedly select tails as a possible outcome? The reason is in the heart of the discussion in this article. An assumption, an incorrect one, led to an impossibility. It led to blindness, therefore, there is minimal to zero chance for an accurate prediction and sustainable success.

In this case, if we flip this coin enough, we can figure out that something is eventually wrong. The problem with this approach is that often, we only have one chance at the apple. Getting it wrong once can have serious consequences.

I set this up to lead you down a path by saying that I have a coin. Your focus on the number of possible outcomes through the basic assumption that I flipped a two-headed coin, likely led you towards blindness. Magicians use this technique all of the time. They prey on our incorrect assumptions and on the fact that we limit the number of possible outcomes to pull a rabbit out of thin air.

We humans are great at connecting dots when information is missing. The downfall of that is it leads to inaccurate assumptions, which lead to consequential actions, which lead us toward unplanned, unanticipated, and often unwanted results.

I recently viewed a photograph of a work site somewhere in the Arctic with the caption, "What do you see?" I took a few moments to think about what was in the image. The conditions looked harsh, very cold, and there was deep snow everywhere. I saw a worker leaving a snow-engulfed facility, large communications equipment, facility exhaust vents barely piercing through the snow, and other facility-related apparatus. There was not much else to see other than the whiteness of the snow introducing the blueness of the sky, or was there?

Two workers leave the facility as they always do. No worries. Nothing has ever happened. One worker decides to rush ahead, to turn around and take a picture of the second worker leaving the facility. It was a beautiful sight. Shortly after returning to their home base, the colleagues decided to view their prized photograph and, lo and behold, there it is. They saw it! Three black dots, one noticeably larger, centered and slightly lower than the other two among the mounds of snow, equipment, and vastness of the sky. These dots identified the unmistakable stare of a very large polar bear on the left side of the image as it stood glancing at them next to an antenna tower. This polar bear was positioned approximately 100 feet from the second worker.

Let's analyze this scenario for a moment. How is it that the photographer and the other employee did not see or expect to see the polar bear? After all, it is the Arctic! The workers stated that, while they knew polar bears were around, they have never seen one so close to the facility in the many years of working there. Never seen one so close! Nothing has ever happened so the risk was not mitigated! Does this sound familiar? These workers made an incorrect assumption; one that could have costed their lives; one that limited the possible outcomes which, by design, restricted their ability to see the danger, and hence they did not. They were blinded to the point of placing themselves in harm's way simply by placing the "nothing has ever happened" filter in place of actuality. Heads or tails, anyone?

While the outcome of an assumption can be inconsequential, for example, being wrong or right about the outcome of a coin toss, the opposite is also true. Your assumptions can convert an otherwise successful approach into a complete disaster. In this case, that bear could have attacked without much effort and without much resistance. Lucky for these two workers, the lessons learned did not require the cost of a life. Always remember: Assumptions are the foundation of blindness and are a precursor to the inevitability of undesirable outcomes.

Blindness as I am referring to here is self-inflicted. By dismissing something as irrelevant or by not considering all of the possible outcomes of actions or inactions, you limit vision and enhance blindness. The result is that expectations are often not met, or the result leads to undesirable consequences.

Assumption-Based Decision Model

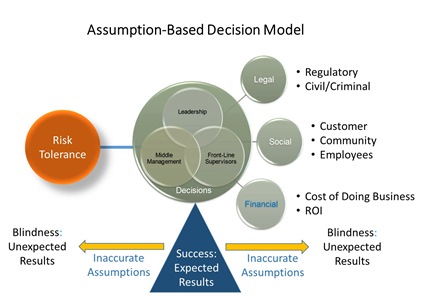

Let's take a look at how most business decisions are made by most leaders at all levels through the use of the Assumption-Based Decision Model. This tool considers risk and basis of decisions to determine if there is an imbalance within an organization that results in blindness towards unexpected results.

The model balances decisions on the pivot point where vision and expected results join forces to deliver operational excellence. Any imbalance in the model causes blindness and unexpected results.

Most decision-based models include the standard legal, social, and financial considerations as they pertain to organizational risk. I will not elaborate on these three factors because most professionals understand the implications of each and their impact on the business. These appear on the right side of the model.

On the left side of the pivot point is risk tolerance. Every organization has a predetermined risk tolerance and each establishes it, not necessarily by policy or documentation, but rather by their visible actions. Often, risk tolerance is expressed in ways that are invisible to leadership but very visible to the workforce and vice versa. High-risk tolerance is, in fact, a storage warehouse for blindness, one that eliminates possible outcomes by the assumptions that limit vision. An example of this is when a leader says safety is important but then proceeds to walk past a "safety shoe required area" without this protection. Another example is when a worker correctly uses personal protective equipment only when the boss is around.

Sometimes, it manifests itself in other ways, such as in a culture where someone else is often responsible for taking action; therefore, there is little to no accountability established. In these examples, the leader and the worker are expressing a high-risk tolerance at the expense of legal, social, and financial factors and are tipping the Assumption-Based Decision Model to the left, toward blindness. On the other hand, when risk tolerance is very low, it immobilizes the organization to the point where work cannot be accomplished. In this case, the model is tipped to the right and the same result occurs, blindness.

Balancing risk tolerance with the three most common decision drivers establishes a higher likelihood of success in regard to experiencing the expected organizational results.

As you can see, assumptions are a powerful factor in establishing clarity of vision or the darkness of blindness. Comprehensive and vetted assumptions are the first step toward driving the desired results.

This means that assumptions can be your friend or foe. The key to success in this regard is to understand the basis for your decision-making process and the risks associated with it.

Vision vs. Blindness

Vision and blindness are often not mutually exclusive. One can be completely contrary to the other and complementary at the same time.

Let's look at the polar opposite relationship of vision and blindness. If you have no vision, then you have blindness. Conversely, if you have no blindness, then you have vision.

When vision and blindness have a polar opposite relationship, we tend to make unconscious assumptions, which leads to unconscious bias, which leads to unmitigated risk. An example of an unconscious assumption is when we leave our homes for work every morning. We inherently make the unconscious assumption that we will arrive safely and on time. We blind ourselves to the fact that how we drive and the condition of our vehicle could significantly impact that end result. We even assume our vehicles will start and the tires will not go flat and the brakes will work and everyone will stop at that red light or stop sign. Most often, few of these are considerations when we leave for work. We transform these into viable assumptions that blind us to the point of perhaps taking an unmitigated risk.

From a purist perspective, vision and blindness do have a polar opposite relationship. In reality, though, both usually coexist in harmony. Vision and blindness can share a complementary relationship when we mitigate our vision by mitigating our blindness. We make conscious assumptions thereby creating conscious bias and ultimately mitigating the risk.

Let's take the driving to work example. If we properly maintain our vehicles, then we mitigate the risk of experiencing a breakdown. If we look both ways at an intersection and pause before proceeding as soon as a traffic signal turns green, then we mitigated the risk of an accident. We made a conscious assumption that predicated itself on the fact that many accidents occur at intersections, so we adopted an inherent bias that intersections are not safe, and we take action to make sure we do not become a statistic. At the same time, we are not worried about our vehicle falling apart (mitigated blindness) because we serviced it per manufacturer recommendations (mitigated vision).

Let's consider how vision and blindness affect non-innovative people or people who are often waiting for things to happen rather than making them happen. When presented with a situation, most people fall into this category by simply seeing the situation as presented. They see a flat line when presented with a flat line and a curved one when presented with a curved one. I call this blindness. Non-innovative people allow themselves to be blinded by the vision of others. These are the "it is what it is" people.

The mindset of non-innovative people is very transparent. I can spot one a mile away simply by the way they approach their work and how they view the world. The inherent mindset of non-innovative people follows a relatively straight line. It is one that believes opportunities just pop up, that great ones are rare, that simply continuing to do what they do will produce opportunities, that someone else is responsible for making it happen. Non-innovative people are in a perpetual waiting pattern for opportunities to appear.

The question is what is the relationship between vision and blindness as it relates to opportunity? To answer this, let's take a look at how innovative people see the world. When presented with a situation, innovative people immediately start the process of looking for gaps and how to fill them. Innovative people view these gaps as opportunities. They have vision. They are not blinded by the inaction typically common to non-innovative people. When presented with a straight line, innovative people naturally see where they can help to make things better. Other qualities of innovative people are initiative and drive. See it, analyze it, design it, build it, sell it, and then improve it. Innovators do not rest, thereby creating incredible opportunities for themselves, their teams, and their employers.

Innovative people are a different breed and there are not many within organizations. The mindset of innovative people is also very transparent. You can spot one a mile away simply by the way they approach their work and how they view the world. The inherent mindset of innovative people follows a relatively wavy line. It is one that believes opportunities are created and are there only waiting to be found. Innovative people believe that moving forward while briefly glancing back at lessons unleashes vision. They take responsibility for making opportunities happen and are in perpetual pursuit of amazing ones, not by chance, but because they willed them to be created.

Optimism by Chance Thinking vs. Optimism by Design Action

Let's redefine how opportunities are created in terms of focus. It is my experience that most people focus on optimism by chance. An example of this is when you hear someone say, "If I work hard, I will be successful." While working hard is an ingredient of success, it is not the only one and limiting the denominator of the statistical equation limits the possibilities available to this mindset. Another example is when you hear, "I am due for a promotion"—in this case, leaving that probability in someone else's hands. Innovative people think differently. They focus on optimism by design. They set up the process for success and are optimistic because they have confidence in their ability to execute it. An example of this is when you hear someone say, "In three months, I will complete this task" or "I have a career plan that spans over the next several years to achieve my professional goals."

Do you have a formal, written career plan that you are following or path designed to get you where you want to be a year, or two, or three from now? If you do not have a career plan in place, consider one. Take control of your destiny by planning for success and innovating your own way into exceeding your goals and aspirations. Opportunity is the delta between optimism by chance thinking and optimism by design action.

Take a Hill for What It Is Worth

This is a true story about David, an entrepreneur, who saw opportunity where no one else did and, despite self-doubt and naysayers, managed to build a highly successful business.

On his way to work early one morning, David noticed a large hill/small mountain for sale. He did some research and found that the property was not suitable for construction. There was too much rock and the cost of constructing on such a property would be cost prohibitive. In fact, that is the reason the owner put it up for sale in the first place. David was still intrigued and asked virtually everyone he knew for their opinion, including family, friends, and acquaintances, as to whether he should buy this property or not. Individual after individual told him he was crazy for even considering this idea. They asked, "Why would you take that financial risk?"

Ultimately, David took the plunge and bought the hill on the optimism that he could make it work and that this decision was either going to make him or break him financially. David somehow saw something no one else could see, an opportunity. He realized the construction market was up in this area and construction materials were in high demand.

Shortly after purchase, David founded a gravel and stone company. Little by little, rock by rock, David chopped away at the hill taking it down foot by foot and selling it as gravel for roadways and concrete and stone material to control erosion. His business took off until the hill was no more and all that was left was flat, rocky land. He recovered his initial investment halfway down the hill. David decided to continue his rock and stone producing company. Rock by rock, stone by stone, he continued until a crater formed out of the once big hill/small mountain. David became a multimillionaire in the process. His friends and family were in awe of what he had accomplished. Everyone thought he was done. There is no raw material left to sell, right? Not David. He identified yet another opportunity no one else dreamed about. What do you do with a hole? You fill it. David started a landfill business and box after box, bag after bag, and bucket load after bucket load, his company filled the hole, all while making more millions. In the end, David converted the property into a very large park and donated it to the city. This is innovation. This is the kind of mindset that delivers performance beyond expectations.

So you see, seeing straight lines when presented with straight lines blinds you to opportunities that lie within. David's family, friends, and acquaintances viewed life in straight lines. David's entrepreneurial vision identified several needs, gaps that needed to be filled. He brought solutions to life that only he recognized. He took a hill for what it was worth and more.

There is a major takeaway here. If it seems as though there is nothing to see, there probably is something big behind it. Preventing opportunity blindness is not about what others see, it is about how you choose to view the world and the actions you take to transform it into something more.

I have seen many professionals in meetings look at organizational challenges as hills that someone else needs to climb and conquer. They seem to forgo the effort of finding gaps and then providing solutions to fill those gaps in ways their organizations consider as value added. It is then this mindset that separates the self-blinded from the visionary.

The path that leads to vision is paved with inquisition. It is outlined with the perpetual drive to search, find, uncover, and rediscover all that others seem to forgo. Look for what is not there in everything, whether that is your safety management system, your career, or your organization’s competitive position in the marketplace.

Process Thinking—a Different Look

A tool that can help you prevent opportunity blindness is process thinking. Let's forgo systems thinking for now because establishing a mindset of vision is very fundamental. Process thinking offers most everything we need to transform the way we view the world around us.

Process thinking is a way to view the world from a systematic point of view and bring into focus the big picture. In it, every outcome is fundamentally the result of a process. For example, in process thinking, all work-related outcomes are the result of their processes, planned or unplanned. The idea is that if an unexpected outcome occurs, it is because this outcome was a resulting option from the process that generated it.

Process thinking asks "how" and "what" and not "why." "How" and "what" questions lead to sustainable process changes and opportunities for improvement. "Why" questions by themselves lead to fault finding and correction of symptoms and not causes.

Process thinking is a method to evaluate complex systems in simpler ways. It is not about why the outcome happened, but rather about changing the process that led to it. This method inherently causes changes to occur at the beginning, at the forefront of what led to the unexpected outcome, versus trying to modify the outcome itself.

As an example, let's consider a serious injury on a tall job and off a small ladder. Traditional approaches will ask, "Why did this happen?" several times until inevitably it leads to disciplinary action or other human behavior intervention. The "why" method typically starts at the event, works its way backward, and focuses on the worker. The process thinking approach asks, "How did this happen?" at the onset of the project. It analyzes the start of the event and works its way forward until the fault in the process is identified and corrected. Processes are much simpler to change than human behavior. In this example, a larger ladder than available was needed. The worker decided to use the smaller one for a myriad of reasons. By fixing the process so only the taller ladder is available at the job site, where feasible, the worker does not have a choice but to use the "right" ladder for the job. Eliminating "wrong" choices as much as possible is the essence of the process thinking principles. Solely relying on human behavior for success is failure assured in most situations.

Process thinking helps you fill the gap between your plan on paper and your plan in action. It helps identify hidden risks so controls can be designed and implemented, action can be taken, and desired outcomes can be accurately predicted. A process always produces varying degrees of success by design, yet we tend to focus on the outputs when unexpected results occur. The fact is that unexpected results are nothing more than options that came to fruition from poorly designed processes.

Leaders who accept accountability for the outcomes (desirable or not) of the processes they influence are better positioned to see and realize the opportunities for advancement of their mission. Focusing away from completely relying on human behavior for success and designing in performance assurances leads to innovation, safety culture improvement, and predictable results.

Human Behavior and Why It is Not the Way to Go

How do most of us decide on what actions to take? This question is often not asked enough, yet it is one of the best indicators of human behavior.

Let's analyze two very similar scenarios to illustrate why relying on human behavior is not the way to go when implementing corrective actions within your safety management system. In other words, why it is not effective to solely rely on human behavior for the success of your safety program.

In both scenarios, you are commuting to work for a very important meeting with clients and your leadership. This meeting could mean the difference between your company significantly growing or your company sliding on its market share. In both scenarios, you are running 15 minutes late in leaving your home. At best, you will make it there on time.

In scenario one, your purpose, your mission, your drive is to make this meeting, no matter what. In scenario two, your purpose, your mission, your drive is to make this meeting safely, no matter what.

What is the likelihood that you will roll through stop signs, run through yellow/red traffic lights, and speed under scenario one? How likely are you to do the same under scenario two?

It is this slight change in focus or purpose that drives significantly different behavior. If we as humans view the consequence of our actions to be low with respect to our point of reference, then we are likely to take that action. If we view the consequence of our action to be high in the same regard, the likelihood is also high we will not take that action. This is human nature. We pause and perhaps avoid a dark alley while casually and with minimal fear walk a well-lit, well-attended, and popular downtown street. If we view the consequence of not wearing our personal protective equipment as low, then we will not likely wear it. If we view the consequence as high, we will wear it.

Human behavior is very consequentially based. We are always weighing the risk of this in an ever-changing emotional environment. Process corrections that rely on consequential and varying viewpoints are destined to have varying degrees of success and failure. Process changes, on the other hand, that rely on systematic enhancements are destined to produce predictable and expected outcomes. Focus on process changes versus human behavior changes and the former will inevitably influence the latter.

There Is a Solution to Everything. . . All You Have to Do Is Find It

Preventing opportunity blindness is about adopting a mindset powered by objectivity, positivity, openness, and the realization that there are gaps, often significant, in every process, every situation, and in everything we do or do not do. The road toward excellence starts with implementing the four "Bs" of business: be brief, be prepared, be inspiring, and be gone. Be brief means get to the point, effectively communicate and demonstrate that you understand and respect the value of time. Be prepared means do the research, get the right facts at the right time, learn the language of your organization and speak it, and understand the value and art of perspective discovery and expectation management. Be inspiring means being pumped about your career, your project, your team, because if you are not, no one else will be, either. Passion is highly contagious. Be gone means go sell your idea, proposal, or improvement plan. Get it done! Make commitments and deliver on them. Be gone means being visible working toward achieving your organization’s mission. Let your work do the talking. As Henry J. Kaiser, the father of modern American shipbuilding, reportedly said: "When your work speaks for itself, don't interrupt."

The road toward excellence continues with building an amazing reputation, one driven by superior performance and trust. Pave this road with powerful partnerships empowered by collaboration as a gateway to sustainable success. Learn the language of finance because it is the universal language of business. Invest in yourself and learn to understand and converse in your organization’s financial terms. In the end, there is a solution to everything; all you have to do is find it.

Conclusion

So, how do you enable vision 20/20 and prevent opportunity blindness? Remember to identify the filters present that are keeping opportunities at bay. Identify these filters by being mindful of the power of assumptions, by applying process thinking principles, and by understanding how human nature actually helps us in the decision-making process. The two-headed coin exercise and the polar bear camouflaged in the snow are two powerful examples of how assumptions can lead us astray, one inconsequential and the other possibly life-threatening.

Recall the major difference between innovative and non-innovative people and how the inherent mindsets of both can drive vision or blindness by design. The true story, "take a hill for what it is worth," demonstrates the unmistakable impact of vision despite all odds and how financial success can come from it.

Empower process thinking and use it to positively change outcomes for good. You may discover a new way to view and conduct your incident investigation process along the way. Leverage how we, as humans, make decisions, and use this phenomenon to open apertures so you can have a wider, deeper perspective of the business world. Drive the road toward excellence to help you start the process of thinking differently and unleash opportunities for yourself and your employer on your journey toward enhanced safety management system performance by design. Look at both sides of the coin and remember to take a hill for what it is worth; others will miss it. Adapt the four "Bs" of business as a matter of course and ask yourself: "Am I seeing straight lines now or something else?"

Dare to think differently.

References

1. Gardner, M.; Steinberg, L. 2005. "Peer Influence on Risk Taking, Risk Preference, and Risky Decision Making in Adolescence and Adulthood: An Experimental Study." Developmental Psychology 41 (4).

2. Graen, G. B., Novak, M. A., & Sommerkamp, P. 1982. "The effects of leader-member exchange and job design on productivity and satisfaction: Testing a dual attachment model." Organizational Behavior & Human Performance, 30(1).

3. International Journal of Business Intelligence Research (IJBIR) 1(4). 2010. "The Importance of Process Thinking in Business Intelligence." https://www.igi-global.com/article/importance-process-thinking-business-intelligence/47194

4. James, W. (1893). "The principles of psychology." New York: H. Holt and Company.

5. Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Ilies, R., & Gerhardt, M. W. (2002). "Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review." Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 765-780.

6. Kepner, Charles H.; Tregoe, Benjamin B. (1965). "The Rational Manager: A Systematic Approach to Problem Solving and Decision-Making." McGraw-Hill.

7. Nightingale, J. (2008). Think Smart - Act Smart: Avoiding The Business Mistakes That Even Intelligent People Make. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1. ISBN: 9780470224366.

8. Nijhawan, Romi (2010). Space and Time in Perception and Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86318-6.

9. Olchowski, A.E.; Foster, E.M.; Webster-Stratton, C.H. (2007). "Implementing Behavioral Intervention Components in a Cost-Effective Manner: Analysis of the Incredible Years Program." Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, Vol. 3(4) and Vol. 4(1), Combined Edition.

10. Pitagorsky, G., PM Times. "The Importance Of Process Thinking." https://www.projecttimes.com/george-pitagorsky/the-importance-of-process-thinking.html

11. Rodriguez, J.A. 2009. Not Intuitively Obvious—Transition to the Professional Work Environment. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN-13: 978-1441515421.

12. Seselj, I., PM Times."5 Tips To Creating A Process-Centric Organization." https://www.projecttimes.com/articles/5-tips-to-creating-a-process-centric-organization.html

13. Schultz, Duane; Schultz, Sydney Ellen. 2010. Psychology and Work Today. New York: Prentice Hall. pp. 201-202. ISBN 978-0-205-68358-1.

14. Wearden, JH; Todd, NPM; Jones, LA. 2006. "When do auditory/visual differences in duration judgments occur?" Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 49 (10).

15. Yarrow, Kielan; Rothwell, John C. July 2003. "Manual Chronostasis: Tactile Perception Precedes Physical Contact." Current Biology 13 (13).

This article originally appeared in the June 2018 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.