CDC Documents Increased Black Lung Cases in Kentucky

The report describes a cluster of 60 cases of PMF identified in current and former coal miners at one Eastern Kentucky radiology practice during January 2015–August 2016, a cluster that was not uncovered by the national surveillance program.

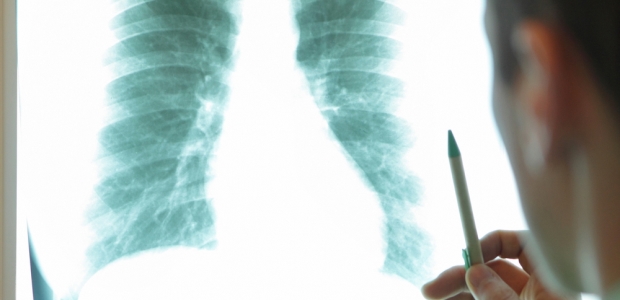

CDC's MMWR on Dec. 16 offered online an alarming report about a surge in cases of Appalachian coal workers' black lung disease. An NPR investigation also probed the increase in this occupational lung disease, which is caused by overexposure to respirable coal mine dust. NIOSH administers the Coal Workers' Health Surveillance Program, a voluntary program with the goal of reducing the incidence of black lung -- pneumoconiosis -- and eliminating its most severe form, progressive massive fibrosis (PMF).

The report describes a cluster of 60 cases of PMF identified in current and former coal miners at one Eastern Kentucky radiology practice during January 2015–August 2016, a cluster that was not uncovered by the national surveillance program. "This ongoing outbreak highlights an urgent need for effective dust control in coal mines to prevent coal workers' pneumoconiosis, and for improved surveillance to promptly identify the early stages of the disease and stop its progression to PMF," the authors point out.

NPR's Howard Berkes obtained data from 11 black lung clinics in Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio that reported a total of 962 cases so far this decade, and he wrote, "The true number is probably even higher, because some clinics had incomplete records and others declined to provide data." The number is more than 10 times higher than what federal regulators report, he wrote.

The MMWR report says on June 9, 2016, a radiologist contacted NIOSH to report a sharp increase during the past two years in the number of PMF cases among patients who were coal miners seen at his practice serving eastern Kentucky counties. This triggered the investigation of the undiscovered cluster of cases. The 60 male patients' mean age was 60.3 years, and their mean coal mining tenure was 29.2 years.

"The finding in the current report of 56 cases among Kentucky residents indicates that many cases were not identified through routine national surveillance; however, this finding is consistent with historically low Coal Workers' Health Surveillance Program participation rates among Kentucky coal miners: during 2011–16 only 17% of Kentucky coal miners participated (personal communication, Coal Workers’ Health Surveillance Program data, October 5, 2016)," according to the report, which adds that the factor or combination of factors that caused the increase, and whether there are more unrecognized cases in neighboring coal mining regions, are unknown.

The authors are David J. Blackley of the NIOSH Respiratory Health Division and colleagues from that division and from United Medical Group in Pikeville, Ky.

"Because PMF takes years to become manifest, the specific exposures or mining practices that led to these cases are also unknown. New or modified mining practices in the region might be causing hazardous dust exposures. While obtaining detailed occupational histories, the reporting physician identified the practice of 'slope mining' as a potential exposure in eastern Kentucky (slope mining involves teams of miners operating continuous miner machines, designed to cut coal and other soft rock, to cut shafts through hundreds of feet of sandstone to reach underground coal seams)," it states. "The sandstone formation underlying eastern Kentucky is >90% quartz, and dust generated during the slope cutting could expose miners to hazardous dust containing high concentrations of respirable crystalline silica. Previous research found that 25 of 37 (68%) Kentucky and Virginia coal miners with 'advanced pneumoconiosis' (defined as PMF or simple coal workers' pneumoconiosis with high small opacity profusion) reported working as roof bolters, a mining job associated with high silica dust exposure. The current investigation was limited to miners with PMF and found that 26 (43%) reported working as roof bolters, and 20 (33%) reported working as continuous miner operators. Operating a continuous miner machine has typically been considered a 'coal-face position' (i.e., a work position located at the face, or seam, of coal), and therefore not a position usually associated with higher silica dust exposures. However, the use of a continuous miner machine during shaft cutting or thin seam coal mining (i.e., occurring when the height of the coal seam requires that rock above and below the coal seam is cut along with the coal) requires cutting through rock and creates the potential for respirable silica exposures, which might explain why working as a continuous miner operator could pose an increased risk for PMF.

"In addition, recent industry trends might have led to a higher number of miners seeking radiographs, either to gather information about their health status or to seek benefits through state workers’ compensation or federal black lung programs. A steep decline in coal miner employment and coal production during recent years has occurred, with 1,501 jobs lost in Kentucky (17.9% of state coal workforce) during the first quarter of 2016. Miners might feel that future coal-related employment is unlikely and that previous barriers to health-seeking behaviors have been removed. For example, in Kentucky a miner has 3 years to file a state compensation claim 'after the last injurious exposure to the occupational hazard or after the employee first experiences a distinct manifestation of an occupational disease in the form of symptoms reasonably sufficient to apprise the employee that he or she has contracted the disease, whichever shall last occur.' Because the earlier stages of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis can be associated with few or no overt symptoms, and because coal mining jobs have historically been among the best-paying in the region, some miners might have chosen to not seek radiographs or other health-related information during the earlier stages of their career to avoid threatening their ability to continue working in the industry."

The authors write that their findings are subject to at least three limitations: They come from a single radiologist's practice, classifications of chest radiographs were performed by a single B Reader who was aware of miners' occupational histories and other clinical data, and the cases weren't identified through standard coal workers' pneumoconiosis surveillance and whether similar clusters of cases exist in other communities is not known.