CDC Museum Opens Exhibit on 2014 Ebola Outbreak

"CDC's Ebola exhibition shows what it was like 'inside the outbreak' for one of the world's worst public health emergencies," said CDC Acting Director Dr. Anne Schuchat, M.D. "I hope people will leave the museum recognizing that, with commitment and will, working together, we can change the world and make it a safer, healthier place for everyone."

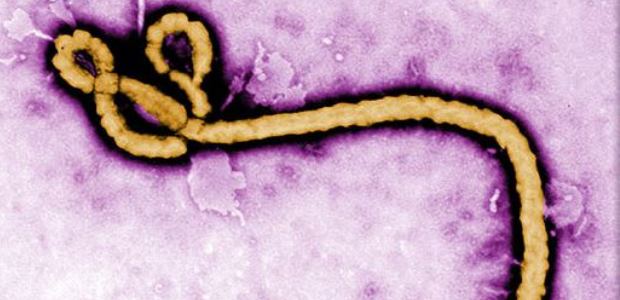

Promising to give visitors a glimpse of "what it was like at ground zero of the worst outbreak of Ebola in history," the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has opened an exhibit at its David J. Sencer Museum on the outbreak that began in West Africa in 2014. The exhibit titled "EBOLA: People + Public Health + Political Will" is open until May 25, 2018, at CDC headquarters in Atlanta; the Sencer Museum is the first U.S. museum to offer an overview of the outbreak that killed more than 11,000 people in West Africa, according to CDC.

"CDC's Ebola exhibition shows what it was like 'inside the outbreak' for one of the world's worst public health emergencies," said CDC Acting Director Dr. Anne Schuchat, M.D. "I hope people will leave the museum recognizing that, with commitment and will, working together, we can change the world and make it a safer, healthier place for everyone."

The exhibit features photographs by some of the world's leading photojournalists that show the severity of the outbreak and the challenges faced by public health workers to bring it under control; there are artifacts such as crosses made to mark the graves of victims, shipping canisters still dusted with West African clay, and helmets worn by motorcycle drivers who delivered samples through the crowded streets.

CDC received its first reports of Ebola virus disease from a remote part of Guinea in spring 2014, and within weeks the outbreak had mushroomed in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. "Thousands were sick and dying and – for the first time in history – Ebola was spreading in crowded urban centers," according to the agency's announcement of the exhibit. "A Liberian traveler brought Ebola to Nigeria; another traveler brought it to the United States. It was clear that without a coordinated, massive response, Ebola would spread exponentially, threatening global health security. CDC and other parts of the U.S. government, the United Nations, the World Health Organization, other governments, private donors, the CDC Foundation, and many international aid organizations mobilized massive resources." It says CDC Museum Curator Louise E. Shaw "knew during the outbreak that history was unfolding and took steps to document it for future generations." The materials, including oral histories, are now part of the CDC Historic Collection.

"We knew that this story needed to be remembered and told," Shaw said. "As CDC employees returned from West Africa, they would stop by and drop off gear, field notes, and personal items they had used while fighting Ebola. These items – along with the photographs – remind the viewer that behind the statistics there are very human stories."

The exhibition is supported by CDC's Office of the Associate Director for Communication, the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Diseases (NCEZID) and Center for Global Health (CGH) and the CDC Foundation. CDC worked with WHO, UNICEF, the World Food Programme, USAID, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Peace Corps to identify photographs, documents, and objects. Médecins Sans Frontières, the International Rescue Committee, the International Organization on Migration, and Riders for Health are among the non-government organizations that contributed to the project.

The museum will host a media day June 28.

The World Health Organization declared on March 29, 2016, that Ebola no longer constituted a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. The agency's Emergency Committee had met for the ninth time via teleconference that day and heard from representatives of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone about their efforts to prevent the Ebola virus' re-emergence and their capacity to detect and respond rapidly to any new cluster of cases. The committee noted that all three countries had met the criteria for confirming interruption of their original chains of Ebola virus transmission -- completing the 42-day observation period and additional 90-day enhanced surveillance period since their last case that was linked to the original chain of transmission twice tested negative.