Page 3 of 4

Sick Building Syndrome: What It Is and Tips for Prevention

"Sick building syndrome" is the name given to a collection of illnesses and symptoms that afflict multiple occupants of particular buildings. The symptoms include sniffles; stuffy noses; itchy eyes; sinus infections; scratchy throats; dry, irritated skin; upset stomachs; headaches; difficulty concentrating; and fatigue or lethargy. The key factors in diagnosing sick building syndrome are a rapid recovery and the disappearance of symptoms after an affected individual leaves the building.

Occurrences are not rare, nor is there a simple solution. Sick building syndrome is common enough that many government agencies have published research on causes and symptoms. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health included it as a recognized health issue1 in its Environmental and Occupational Medicine, Third Edition. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration also calls out sick building syndrome, which it refers to simply as "indoor air quality," and makes several recommendations for remediation, especially increased ventilation.

Causes of Sick Building Syndrome

During the first energy crisis in the 1970s, builders and building owners took steps to reduce energy consumption in office buildings. Measures included increased insulation, building wraps, weatherstripping doors, and using insulated double- and triple-pane windows, among others. In many cases, buildings were erected or renovated to include windows that couldn't open, to minimize loss of heated or cooled air. The result: Some modern buildings feel as if they are airtight.

Building décor also contributes to the issue. Many paints, carpet fibers, furniture, and even wallboard off-gas noxious fumes, sometimes for years after installation. These products may emit formaldehyde, acetic acid, or volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other chemicals. Modern office equipment such as copiers and electrostatic air cleaners add to the problem by adding ozone to the mix. Mold or mildew from damp conditions also create air quality problems. Manufacturing processes and material-handling equipment may add hydrocarbons or smog, and many chemical cleaning agents give off harmful vapors. The result is a chemical stew in the air that makes people ill—with sick building syndrome.

How to Identify Sick Building Syndrome

There is no specific medical test to diagnose sick building syndrome. Physicians usually treat the symptoms individually, but the real identification of a "sick building" is subjective. Telltale clues include increased absenteeism among the building occupants, a large number of occupants complaining about vague but similar symptoms, and a common history of symptom resolution when people are not in the building.

To help identify whether your building is causing or contributing to the problems, look for these common characteristics:

- Symptoms occur when occupants are in the building or a specific area of the building.

- Symptoms dissipate or disappear when affected persons are away from the building or area.

- Symptoms coincide seasonally with the use of heating or cooling equipment.

- Multiple co-workers have similar complaints.

If the majority of people find their symptoms clear up when they are out of the building, it may be safe to assume the building air quality is a contributing factor to illness. You have a "sick building." Now what?

Resolving Sick Building Syndrome

OSHA and most other government agencies that have weighed in on sick building syndrome believe the problem is primarily related to indoor air quality. NIOSH research breaks down how frequently poor indoor air quality could be traced to specific sources:

- Inadequate ventilation: 52 percent of cases

- Contamination from inside building: 16 percent

- Contamination from outside building: 10 percent

- Microbial contamination: 5 percent

- Contamination from building fabric: 4 percent

- Unknown sources: 13 percent

According to OSHA, improving ventilation and eliminating sources of smog or contaminants in the air are the best actions to take if you suspect you have a sick building. Here are some key actions to start you off:

1. Clean up wet or damp areas. Mold and mildew aggravate allergies and cause irritation even in non-allergic individuals, so getting rid of them in the building may help. Seek out any sources of dampness or standing water and repair all leaks. Clean up all remaining dampness. Set up fans in the dank areas to speed-dry any remaining water and wash away visible mildew or mold with a solution of bleach and water or a commercial mold cleaner if the affected area is small enough.

Be sure to rinse and dry the area completely after cleaning, and wear goggles, a mask, and gloves when using any bleach solution. After a thorough cleaning, if you still see visible signs of mold or smell mildew, you may need to bring in a mold remediation expert to help resolve the problem permanently.

If the area is large or the problem is extensive, you should not attempt to clean it yourself. In that case, call a mold remediation specialist, who will have the proper training and equipment to do the job correctly.

2. Install HVLS fans for ventilation. OSHA states2 that the most effective solution for indoor air quality issues is ensuring an adequate supply of fresh air through natural or mechanical ventilation. It recommends following the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers' (ASHRAE) recommended airflow rate of 5 cubic feet per minute (CFM) per person in a standard office environment and up to 15 CFM in smoking areas or areas adjacent to manufacturing or warehousing areas.

High-volume, low-speed (HVLS) fans can move up to 425,000 CFM and also can make the space feel up to 10 degrees warmer or cooler without your touching the HVAC thermostat settings. The large blades of these fans enable a high volume of air to move, while reversing the fan in the cooler months will eliminate drafts that can make working under traditional fans uncomfortable.

The best HVLS fans are reversible, so they work for both winter and summer. Some systems even allow you to control multiple fans remotely from a single control box, making HVLS fans an ideal solution for efficiently and effectively improving indoor air quality. Make sure any fan you are considering meets ASHRAE standards for air movement.

Traditional box fans or standard ceiling fans also can provide movement of air that gives the illusion of freshness, but they often create unpleasant drafts and may not provide the outdoor air volume necessary for fresh indoor air. In addition, they are frequently noisy, making them unsuitable for quiet office environments.

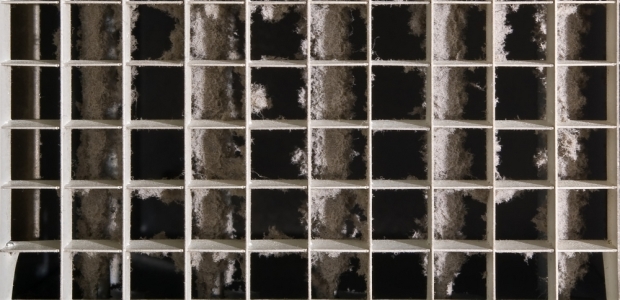

3. Perform regular HVAC maintenance. HVAC systems require regular maintenance, including changing filters and regular tune-ups. If you haven't been performing the required maintenance, now is the time. You may need to bring in a service firm to do the required tune-up and to make sure the system is operating at peak efficiency. Also, the service technician usually can check to ensure the equipment is not creating any emissions it shouldn't. Changing the filters will improve efficiency and increase airflow. Once you have the equipment working efficiently, you should create and follow a regular maintenance schedule.

You also might want to consider having your ducts cleaned, or at least inspected. If they contain mold, dirt or vermin, increasing the airflow through them actually might exacerbate your sick building problem.

4. Install air cleaners or filters. If your business environment includes equipment that releases ozone or other air contaminants, you might want to install air cleaners or filters. OSHA recommends air cleaners for smoking areas, so if you provide an indoor smoking area, you should look into this option. You also might consider this as a solution for areas that include printers or copiers suspected of causing a problem or for doorways between manufacturing and office areas, where fumes and emissions may enter.

This solution is best for smaller, more confined areas of a building. If you suspect your problem covers a large part of the building, this solution may not provide as much relief as installing HVLS fans that can cover a greater area more effectively.

5. Open windows to improve natural air circulation. Many modern office and business buildings do not have windows that open. If you are lucky enough to have operable windows, consider opening them for at least part of the day to provide natural ventilation and a greater flow of fresh outdoor air.

Do not open windows that face high-traffic areas, industrial areas, or areas that leave them vulnerable to rain or wet weather. Opening windows where these air quality hazards exist can do more harm than good as you seek to resolve your sick building issues.

6. Choose interior materials carefully. Many modern building materials and interior furnishings emit harmful substances for months or years after installation. Choosing materials that emit harmful substances during a renovation may actually create a sick building issue where none existed previously, so it makes sense to take the time to choose wisely.

Look for paints with low VOC ratings and carpeting or furniture made from natural materials or that do not have large quantities of noxious chemicals. Pay special attention to ratings for formaldehyde, styrene, 4-PC, and VOCs. The Carpet and Rug Institute and the Environmental Protection Agency worked together to create standards for these substances, so look for the conformance label when buying new carpets. EPA has worked with the furniture, building, adhesives and paint industries to create similar standards and certifications as a guide to consumers looking for the healthiest options.

Conclusion

Indoor air quality can have a profound effect on the health and productivity of your employees or building occupants. To safeguard their health, it's a smart business move to do all you can to alleviate or prevent sick building syndrome. HVLS fans, mold remediation, and thoughtful selection of materials during renovations can help to clear up or prevent sick building syndrome problems.

References

1. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/nioshtic-2/20000157.html

2. https://www.osha.gov/dts/osta/otm/otm_iii/otm_iii_2.html

This article originally appeared in the October 2016 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.