Page 2 of 3

Combustible Dust Basics: How to Collect a Sample and What Does a Go/No-Go Test Mean?

We've been blogging and writing a lot recently on the basics of combustible dust. Makes sense; after all, what safety professional knows exactly how much of their particular dust, in their particular facility, under a certain set of circumstances is OK? And if you don't yet have a dust collection system, how do you know what you need? Even if you have a collector, do you have the proper Process Hazards Analysis (PHA) to understand your dust’s potential for explosibility?

Plant and facility safety professional customers often will call and say they think they need a dust test but do not know what the next step is. They'll ask, "How do I collect a sample?" "What is a Go/No-Go test?"

While we offer a list of testing services to determine the deflagration hazards of dust samples per ASTM International, OSHA, National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA), and UN (United Nations), knowing the basic tests can go a long way for tackling your safety needs.

In Professor Paul Amyotte's "An Introduction to Dust Explosions: Understanding the Myths and Realities of Dust Explosions For a Safer Workplace," Amyotte offers a section on Practical Guidance:

These observations help to explain the advice given by experienced industrial practitioners on the matter of acceptable combustible dust layer thicknesses. Their comments, although anecdotal, have a firm foundation in the physics and chemistry of dust explosions. Scientific underpinning by the aforementioned difficulties in physically dispersing and chemically reacting excessively thick dust deposits is intrinsic to the following expressions:

- There's too much layered dust if you can see your initials written in the dust.

- There's too much layered dust if you can see your footprints in the dust (Anonymous, 1996. Personal communication, with permission).

- There's too much dust if you can’t tell the color of the surface beneath the layer (Freeman, R., 2010. Personal communication, with permission).

- I tell my plant manager to write their name on their business card. It's time to clean up when they can’t read their name because of layered dust. (Anonymous, 2012. Personal communication, with permission).

So, what is a combustible dust? You might be wondering this before you worry about how to ship it off to be tested. Per the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety: Essentially, a combustible dust is any fine material that has the ability to catch fire and explode when mixed with air. Combustible dusts can be from:

- most solid organic materials (such as sugar, flour, grain, wood, etc.)

- many metals, and

- some nonmetallic inorganic materials.

Some of these materials are not "normally" combustible, but they can burn or explode if the particles are the right size and in the right concentration.

Therefore, any activity that creates dust should be investigated to see whether there is a risk of that dust being combustible. Dust can collect on surfaces such as rafters, roofs, suspended ceilings, ducts, crevices, dust collectors, and other equipment. When the dust is disturbed and under certain circumstances, there is the potential for a serious explosion to occur. The buildup of even a very small amount of dust can cause serious damage.

OSHA defines combustible dust as "a solid material composed of distinct particles or pieces, regardless of size, shape, or chemical composition, which presents a fire or deflagration hazard when suspended in air or some other oxidizing medium over a range of concentrations."

Which Workplaces Are at Risk for a Dust Explosion?

Dust explosions have occurred in many different types of workplaces and industries, including:

- Grain elevators

- Food production

- Chemical manufacturing (e.g., rubber, plastics, pharmaceuticals)

- Woodworking facilities

- Metal processing (e.g., zinc, magnesium, aluminum, iron)

- Recycling facilities (e.g., paper, plastics, metals)

- Coal-fired power plants

Dusts are created when materials are transported, handled, processed, polished, ground, and shaped. Dusts are also created by abrasive blasting, cutting, crushing, mixing, sifting, or screening dry materials. The buildup of dried residue from the processing of wet materials also can generate dusts. Essentially, any workplace that generates dust is potentially at risk.

So, do you have something that might be hazardous in your facility? You need a simple test to find out whether it's explosible. That's a "Go/No-Go Test." Collect a dust sample and find out if and what it takes to ignite. Air sampling is not necessary to determine whether or not a dust is combustible.

Dust testing is performed on the sample as it is received ("as received") from your facility. It may be screened to less than 420 µm (40 mesh)--OSHA's and NFPA's demarcation of a "dust"--to facilitate dispersion into a dust cloud. Particle size may vary widely, depending on the sample.

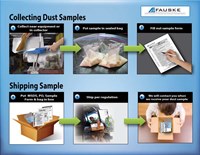

It's easier than you think:

* Please note: If you suspect you may have an electrostatically charged dust, collect the sample by using a plastic-coated shovel or scoop.

A Go/No-Go Screening Test, based on ASTM E1226, "Standard Test Method for Explosibility of Dust Clouds," is an abbreviated, set explosion severity testing at two or more dust concentrations to determine whether the sample is explosible. This test is generally performed with samples tested "as received" or sieved with more than 100 grams (approximately 0.25 pounds) of sample less than 420 µm required.

A Combustible Dust Screening Test is based on VDI2263 and UN 4.1 combustion testing. This test is to determine whether a dust in a pile supports self-sustaining flame propagation. [More than 30 grams (approximately 1 ounce) of sample less than 420µm required; more than 300 grams (approximately 0.67 pounds) of sample less than 420 µm required if testing metal dusts.]

This chart discusses the outcomes for your tested dust. If your test sample is a "Yes, it explodes," then further tests can be run to determine how quickly and how severe the explosion will be (K

St/P

max Test), followed by testing what concentration of dust in the air will cause a risk of explosion (MEC Test). Next, another test can determine whether a spark will cause an explosion (MIE Test).

But what if your Go/No-Go test result is a "no"? We next look at what temperature it will take make your dust ignite. To find the Minimum Autoignition Temperature (MIT) of a dust cloud in the air, the MIT tests the minimum temperature that would cause your dust cloud to ignite. Next is the Layer Ignition Test (LIT), which determines the hot-surface ignition temperature of a dust layer. Finally, a VDI 2263 burning behavior test is conducted to determine whether a dust will burn and, if it does, how quickly it will spread. It is followed up by a UN 4.1 Burn Rate test for additional confirmation.

All of these tests start with the Go/No-Go Test. A comprehensive Process Hazards Analysis (PHA) can apply your test results to real-world scenarios at your facility. Better to know what you are dealing with so you can plan safely!

Here are some other tests run for dust explosibility screening:

- Go/No-Go Screening + Combustible Dust Screening Package. Both tests run in tandem as a screening package.

- Sample Characterization Test. It includes determining the sample moisture content and particle size distribution (more than30 grams of sample less than 420 µm required).

- "Hard-to-ignite" Explosibility Test. Tested as above, but with a 400 J ignition source [more than100 grams (approximately 0.25 pounds) of sample less than 420 µm required]

Unless otherwise instructed, dust testing is performed on the sample as it is received ("as received") from your facility, as mentioned earlier. It may be screened to less than 420 µm (40 mesh)--OSHA's and NFPA's demarcation of a "dust"--to facilitate dispersion into a dust cloud. Particle size may vary widely, depending on the sample.

Furthermore, note that, per ASTM recommendations (and some NPFA requirements), samples should be tested at a particle size less than 75 µm and less than 5 percent moisture. Please note that testing materials in a method not complying with the ASTM/EU recommendations may produce explosion severity and explosion sensitivity data that is not considered conservative enough for explosion mitigation design.

This article originally appeared in the May 2014 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.