Israel Dvorine: Pioneer in Color Vision Testing

Defective color vision is a risk factor as the number of occupations relying on color grows.

- By Lloyd Powell

- Jun 01, 2011

This article describes the first U.S. color vision test, which was developed during World War II through the initiative and pioneering dedication of a remarkable man -- Dr. Israel Dvorine. We mention the technical and commercial aspects that Dvorine experienced to achieve optimal reproduction of color illustrations, known as pseudoisochromatic plates. Key to this article is the relevance of color vision in the workplace, crucial to Dvorine's endeavors.

A pseudoisochromatic color vision test comprises a number of colored plates, each of which contains a pattern of dates that appear randomized in color and size. Within the pattern are other dots that form a number or symbol visible to those with normal color vision and invisible, or difficult to see, for those with a color vision defect. Although a complete test consists of a higher number of plates, the existence of a deficiency is usually clear after a few plates. Continuing testing using more plates gives a more accurate diagnosis of the severity and nature of the color vision defect.

The world's first color vision test based on pseudoisochromatic plates, and using a chromolithograph technique, was developed by Jakob Stilling in 1875 in Germany. The Stilling plates were reliable only in daylight and were improved upon by Dr. Shinobu Ishihara, a Japanese ophthalmologist, who created the Ishihara Color Vision Charts in 1917 while teaching at the University of Tokyo.

The First American Color Vision Test

The attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 caused much activity among eye care professionals and manufacturers because it was clear that the U.S. armed forces could no longer obtain the Ishihara test, the standard at that time, to fulfill the rapidly increasing requirement for color vision testing. Testing was needed for many additional U.S. military, commercial marine, and aviation personnel. As a quick substitute, the American Optical Company commenced printing the Ishihara and Stilling test plates from photographic copies. However, the quality of reproduction was sub-optimal.

In the early 1940s, Dvorine began to experiment with plates that he painstakingly painted with watercolors on cards in an attempt to create his own test. It took him about a year of trial and error and testing on more than 70 volunteers to complete enough cards. The next major production challenge was to have his original cards faithfully reproduced on a printing press. This was also no easy matter; he again exercised great patience during a period of more than a year in seeking and instructing a plate maker, selecting the right inks, and finally developing a reliable printer. This proved so complex that he found it necessary to learn color printing and be present at the printing press to ensure accurate color registration with zero tolerance.

Dvorine had great respect for Dr. Louise Sloan, an eminent scientist at Johns Hopkins Hospital and developer of the Sloan eye charts, who had praised a number of the Dvorine charts in an academic article. She later tested and selected charts for the second edition of Dvorine's plate set booklet. In 1944, when the second edition was ready (with the title "Dvorine Color Perception Testing Charts"), Dvorine fought a lengthy battle with various departments of the U.S. government to gain approval. He won, and his set of plates became the replacement of the low-quality Ishihara and Stilling copies. Subsequent editions of his test plates were ring-bound with the title "Dvorine Pseudo-Isochromatic Plates" and provided with instructions and a Recording Form.

Over the years, and as is often the case with large corporations, Dvorine's publisher went through various mergers. The most recent publisher has discontinued the Dvorine booklet due to the inability to reprint the test without Dvorine's presence. Most U.S. government and university users now specify the HRR (Hardy, Rand, Rittler) 4th Edition color vision test, which is further described below.

Other Pseudoisochromatic Plate Tests

The most frequently used pseudoisochromatic plate tests today are the Ishihara and the HRR 4th Edition. The HRR test plates originally were printed in 1953 and again in 1955 by American Optical as the result of developments that began in 1943 by a committee of color experts. In 2004, Richmond Products Inc. of Albuquerque, N.M. had the plates re-engineered to produce the present 4th Edition with the help of Dr. Jay Neitz, Dr. Maureen Neitz, and Dr. James E. Bailey. (Jay Neitz, Ph.D., and Maureen Neitz, Ph.D., respectively, are Bishop Professor and Hill Professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Washington, Seattle, Wash. Dr. James E. Bailey, OD, Ph.D., is professor, Department of Basic and Visual Sciences, at the Southern California College of Optometry, Fullerton, Calif.)

The most frequently used pseudoisochromatic plate tests today are the Ishihara and the HRR 4th Edition. The HRR test plates originally were printed in 1953 and again in 1955 by American Optical as the result of developments that began in 1943 by a committee of color experts. In 2004, Richmond Products Inc. of Albuquerque, N.M. had the plates re-engineered to produce the present 4th Edition with the help of Dr. Jay Neitz, Dr. Maureen Neitz, and Dr. James E. Bailey. (Jay Neitz, Ph.D., and Maureen Neitz, Ph.D., respectively, are Bishop Professor and Hill Professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Washington, Seattle, Wash. Dr. James E. Bailey, OD, Ph.D., is professor, Department of Basic and Visual Sciences, at the Southern California College of Optometry, Fullerton, Calif.)

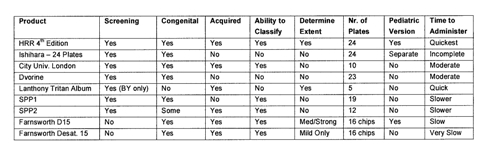

Optometrists and ophthalmologists the world over acknowledge the HRR 4th Edition as the most accurate pseudoisochromatic test available today, and superior to the Ishihara test. The table in this article summarizes the main color vision testing methods in current use.

Occupational Aspects

In addition to congenital (genetic) color vision defects, many pharmaceutical products that deal with the nervous system can be the cause of acquired color vision defects. Defective color vision is a risk factor as the number of occupations relying on color grows. More and more tasks are increasing in complexity along with stricter work safety standards. The most obvious types of job functions where color vision is critical to the safety of personnel, or the environment, are those where color signage, alarms, wiring, or coding are used, especially on hazardous substances and road safety.

Conclusion

This article highlights how sensitive and vulnerable our eyes are with respect to many occupations. Too often, as with our general health, our ability to see is taken for granted. Fortunately, we are continually reminded to take care of our eyes, especially by optometrists and ophthalmologists. It is important to note that there is an ongoing need for trained eye physicians and nurses and for research in both vision acuity and color vision, particularly in more effective occupational screening and testing. Moreover, the article underscores the significant contribution made by Dr. Israel Dvorine and the growing importance of occupational color vision testing.

This article originally appeared in the June 2011 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.