The Economics of Workplace Safety

Numerous case studies revealing the positive relationships between safety and productivity are backed up by organizations that gather global statistics on accidents and incidents.

It isn't a question of "if," it's a question of "when" your business will experience a serious workplace accident or enterprise-wide disaster. There are many things that can be done to extend the "when," even to the point of making "when" an almost statistical impossibility. Using conveyor design as an example, this article provides a useful methodology—which can be applied to any aspect of safety—for justifying investments to reduce the probability and severity of accidents.

Safety in the workplace is not a modern idea bred by government regulation; it is a common-sense idea as old as the first quarry. In this day and age, safety is a key factor in worker protection, reduced insurance rates, and a lower total cost of operation. However, operating budgets are often so tight, many people within an organization find themselves asking:

- How does the Maintenance or Operations Manager convince the Plant Manager to spend money from the annual budget for safety improvements?

- How does the Plant Manager influence corporate decision-makers to prioritize safety improvements?

Prior to installation of safety equipment and implementation of corresponding procedures, there are cultural and structural obstacles to achieving a lasting solution. The main culprits are the almost universally used Low Bid process, variations in reporting incident statistics between industries/countries, and the Generally Accepted Accounting procedures (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

Striving for Less

The conventional approach dictates that an organization should spend only enough to meet the minimum regulations needed to maximize production. Planning safety upgrades based upon price alone results in the lowest-quality equipment achieving the minimum compliance—often with no reasonable options to rectify the problems other than spending more on another solution—rather than focusing on long-term life cycle cost. So in reality, accidents caused by shortsighted and economically driven solutions harm people, degrade the environment, and reduce the company’s bottom line.

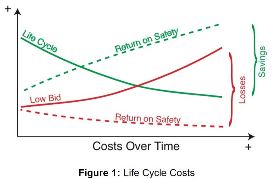

Often when companies buy on price (Low Bid), the benefits are short lived, and costs often increase, resulting in a loss over time. In contrast, when purchases are made based on lowest long-term cost (Life Cycle Cost), benefits usually continue to accrue and costs go down, resulting in a net savings over time. [Figure 1] In order to win the bid on price, suppliers only have to meet minimum quality and safety requirements, when a little additional investment for safer and more reliable equipment will usually result in a safer operation that is sustainable: easier to service, longer life, with lower costs to maintain.

Many companies tout a focus on safety, but few fully achieve the goal. Giant billboards at plant entrances proclaiming world-class compliance with quality and safety standards may shade a different reality inside the plant. Glossy annual reports with safety slogans and sustainability statements look nice for shareholders and investors but are often little more than words on a page. Behind the front gates and the annual reports the message is clear: Produce or be replaced.

Some companies go beyond the window dressing by continuously improving the safety culture from the top down. Organizations that embrace safety show significant performance advantages over the competition. The proof is reflected in safety, productivity, and environmental records, along with above-industry-average financial returns and higher share prices.

Tangible Intangibles

Driven to report direct or tangible numbers that can be documented and are within the "GAAP or IFRS Rules," current accounting (and reward) systems incentivize financial managers to seek the lowest possible expenditures on safety. Justifying safety investments is greatly enhanced by quantifying what most financial managers refer to as "intangible costs." With direct costs being the focus of decades of cost reduction programs, there is little direct expense left to cut and apply to safety.

Intangible costs are calculated by identifying unquantifiable expenditures and relating them to a known source or tangible projected outcome. For example, an unsafe workplace can yield intangible costs such as a loss of productivity due to sagging employee morale and high turnover, which can result in higher tangible costs for hiring and training.

Intangible costs are not entirely indefinable or theoretical; they are merely less tangible than direct costs. Government agencies commonly assign intangible costs to justify regulations intended to improve safety. Economic impact statements are used by regulators to justify the tangible cost to industry by weighing the intangible impact—and projected long-term cost—on society. However, managers and accountants have been trained to think about saving direct costs to justify investments.

Traditionally managers with monthly budgets cut direct costs to support short-term investments and stay within annual spending limits. Long-term investments that don't fit current institutional strategies for spending typically don’t make the capital expenditure list. The private sector’s stubborn adherence to the bottom line and disregard for intangible costs of risk are some of the reasons that efforts to elevate safety to a reasonably acceptable level have plateaued.

Equipping for the Future

Despite bulk material handling being one of the most globalized industries, there are no standardized methods of measuring safety. This makes industry-wide safety performance comparisons and defining best practices very hard to implement.

Conveyors and other process systems are designed to handle a specified range of raw material properties and volumes. However, to improve financial returns, it is common practice for bulk material handlers to revert to purchasing lower-quality raw materials and increasing capacity or to cutting maintenance staff and budgets. Without forethought to the cost of future modifications, operators often find that cheaper equipment cannot be changed or maintained to work efficiently under the new conditions. When conveyors don’t operate efficiently, they have unplanned stoppages, release large quantities of fugitive materials, and require more maintenance. Emergency breakdowns, cleaning of excessive spillage, and reactive maintenance all contribute to an unsafe workplace.

Safety is a continuous improvement process of risk reduction that typically shows results over a longer period of time than the typical plant manager's budget cycle. Risk can be stated as the probability of an incident multiplied by the severity of the incident. Severity can be measured in terms of the cost, so improving safety is an exercise in reducing the probability or exposure and the severity.

Safety Pays

Literature and research offer many pieces of the puzzle on how safety pays, showing the relationships between design and a clean and efficient conveyor. Numerous case studies revealing the positive relationships between safety and productivity are backed up by organizations that gather global statistics on accidents and incidents. Using this information to justify investments in safety requires a more sophisticated financial analysis and data. The simple formula for return on investment (dividing savings by cost) does not capture the potential savings from safety investments.

Martin Engineering's recently published book "FOUNDATIONS™ for Conveyor Safety" provides a road map for justifying investments in safety. When specific data isn't available, the book provides numerous references and global averages for conveyor safety that can be used to reasonably estimate the benefits of investments in safety. The financial analysis approach depends upon the potential benefit being sought.

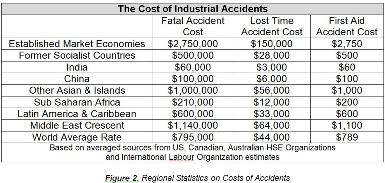

Many companies don't want safety information publicized, and the costs are spread out in accounts such as employee benefits, insurance, or reserves accounts, making objective analysis difficult. However, this topic has been widely studied by academia, and while opinions vary, there are enough valid studies that the results can be averaged. For example, several organizations provide detailed and regional statistics on the cost of accidents. [Figure 2]

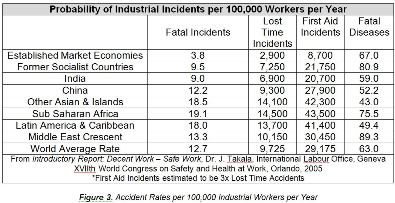

Lacking specific historical data, managers can turn to numerous reliable sources that provide the probability of accidents and incidents that can be used to estimate tangible and intangible future costs. [Figure 3]

"FOUNDATIONS for Conveyor Safety" contains examples that can answer the two questions posed at the beginning of this article. Managers at every level of the organization will be able to see how an engineering firm might convince an owner to spend more on design to improve future safety using the statistics from Figures 1 and 2 or using actual data (in whole or in part) in conjunction with these statistics.

The financial technique used to compare options is called a "net present value" (NPV) analysis. Most spreadsheet programs have a function that can calculate NPV once the proper information is entered. Basically, NPV compares different investment options with varying costs and savings (cash flows) over time by discounting them by the company's cost of money. Another way of thinking about this is that the discount rate adjusts for the cost of money over time, so different alternatives in today's money can be compared objectively.

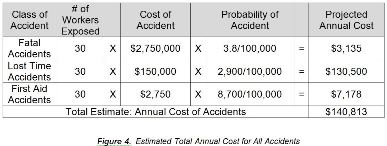

For example, a company's internal risk analysis reveals that a facility will have 30 workers exposed to conveyor hazards. The estimated probability of the different classes of accidents (fatal, lost time, and first aid) is multiplied by the cost of these accidents to reveal what could be invested to reduce the incident rate by half. [Figure 4]

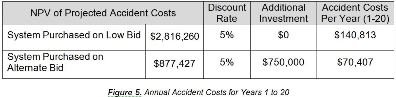

Assuming the life of the conveyor is 20 years and the cost of money (discount rate) is 5 percent, the available additional investment would be about $750,000 more in design time to accomplish the 50 percent improvement in safety. By choosing the lowest-priced bid in order to meet the minimum safety requirements, the short-term expenditure ends up costing considerably more over the 20-year lifecycle. [Figure 5]

By spending $750,000 more to exceed the minimum safety and design requirements and reduce the accident rates by 50 percent, the annual projected cost of accidents drops from $140,813 to $70,407.

Measured in today's dollars—including the additional investment of $750,000—the projected savings over the 20-year term at 5% are about $1.2 million by investing more upfront. By adjusting for indirect costs and including them in the estimated direct cost of accidents, a more in-depth analysis can be made. The results can be modified further by applying judgment factors for the likelihood of the savings being realized. If, after further analysis, the savings are found to be less—perhaps only a 25 percent reduction in the cost of accidents—the up-front investment is still justified over the long term.

Conclusion

The same technique of comparing the current situation to future needs based on additional investments and savings can be applied to a wide range of circumstances that are known to affect safety, such as improving availability, improving equipment reliability, or reducing fugitive material emissions. Typically, safety investments take time to produce results, so a minimum of five years of cash flows (costs – savings) should be analyzed for each investment option.

With a little practice, the NPV approach becomes easy to use and understand. Maintenance, Operations, and Plant Managers employing these techniques may find that it is easier to convince decision-makers to engage in a longer-term safety strategy. Even though it takes a little more effort to collect data and do a financial analysis, in the end, NPV consistently proves that SAFETY DOES INDEED PAY.

This article originally appeared in the October 2018 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.