Preparing for the Silent Workplace Catastrophe

Given the known prevalence of SCA, prudence dictates recognizing cardiac arrest in the safety planning process.

- By John Ehinger

- Nov 01, 2013

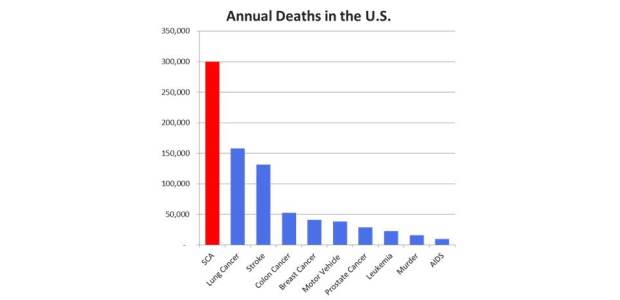

Killing more than 300,000 people in the United States each year, sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is a remarkably underappreciated public health issue. Because it can strike anyone at any time, preparation to address this exposure in the work environment is prudent from a traditional safety perspective. Importantly, cardiac emergency response planning also makes sound business sense.

While thousands of youths die each year from SCA, the risk of incidence increases dramatically as we grow older, especially as underlying heart disease is the leading cause of cardiac arrest. The number of workers aged 55 and older increased 60.8 percent from 2000 to 2010 and is forecast to jump another 38 percent by 20201. On top of this, the population considered obese is cresting past 35.7 percent2. The confluence of these prevailing age, work, and health trends underscores the burgeoning need to confront SCA in the workplace.

Preparation is Critical

With 98 percent of lay adults understanding that automated external defibrillators (AEDs) deliver a shock to restore normal heart rhythm in SCA victims and 60 percent being familiar with cardiopulmonary resuscitation3, the ability to provide required lifesaving aid in public settings is no longer an aspirational goal. It is now something that can be pursued and realized by the public at large.

While the tactical actions required to save an SCA victim are well understood and can be easily implemented, time is the enemy in an SCA event. Survival rates decrease by approximately 10 percent for each minute that elapses without intervention4 and without early intervention, SCA survival rates are less than 8 percent. Thus, both planning and training are essential to delivering positive outcomes when SCA strikes.

Recognizing this, the American Heart Association has prescribed its "Chain of Survival" to maximize lifesaving outcomes in cardiac arrest events, which enumerates the following steps:

1. Immediate recognition of SCA and activation of emergency response systems

2. Early "hands-only" CPR

3. Rapid defibrillation

4. Effective advanced life support

5. Integrated post-cardiac arrest care

Given the logistical realities and timing of EMS response in the vast majority of circumstances, lay action prior to EMS arrival is the only viable means of saving an SCA victim and preventing permanent disability. Of the five links in the chain, the first three are both relevant to and necessary for lay responders.

In theory, none of the three lay activities is complicated, and today's AEDs are exceptionally easy to use5, but when theory must be put into action, proper planning, basic training, and communication protocols are critical to enabling lifesaving results.

Substantiating the value of preparation, research was conducted on a number of Las Vegas casinos that had implemented robust AED programs, including training of dedicated employee responders. The study found that the casinos' programs enabled a mean response time of 2.9 minutes (versus 9.8 minutes for paramedic arrival). More importantly, victims witnessed in ventricular fibrillation who received a shock within three minutes enjoyed a survival rate of 74.2 percent versus 49.1 percent for those who received a shock after three minutes. Clearly, these statistics underscore the need for immediacy of response6.

Enterprise Value Benefits

The lifesaving benefits of integrating a well-structured cardiac emergency response protocol with other site safety and disaster preparedness programs are self-evident: AEDs can save lives. OSHA recognizes this, stating: "All worksites are potential candidates for AED programs because of the possibility of SCA and the need for timely defibrillation. Each workplace should assess its own requirements for an AED program as part of its first-aid response."7

While lifesaving may be the central reason for implementing such a program, proactively addressing the issue of cardiac arrest in the workplace has additional and often underappreciated benefits. A 2009 American Society of Safety Engineers Foundation study confirmed a tie between safety and morale, noting that companies with high morale also effectively address psychological safety, providing employees with peace of mind8.

Although employees are often the focus of site safety preparations, and rightfully so, employees are not the only beneficiaries of sound practice and risk management. All of those who may frequent a location -- customers, vendors, and other visitors -- also stand to benefit from these efforts. Importantly, this second group is external to the organization and therefore wields a powerful, direct influence on an entity's reputation and brand.

Yet beyond employees, customers, vendors, and the many individuals who may interact within a given workplace, organizations must also consider broader oversight when addressing risk and reputation. As Elizabeth Lux wrote for The Wall Street Journal in 2010, "Few investors ask about reputation at the annual general meeting. Until, that is, something goes horribly wrong."9 While investors are often first concerned with the bottom line, it is important to recognize that planning and preparation for cardiac arrest scenarios need not be expensive or excessively time-consuming. Equally, because sound preparations include a well-constructed communication strategy, the very preparations themselves can generate value for the enterprise -- and drive bottom-line results -- because they represent a visible, tangible commitment to the welfare of employees, customers, and visitors.

The value of these prophylactic efforts is only enhanced when they are successfully activated. Following a lifesaving event within a workplace, many organizations find themselves inundated with flattering coverage in TV, print, and other media outlets and, perhaps more importantly, the Internet, specifically in social media channels.

Considering the nature and volume of information available to the public today, the speed by which it travels, and the permanence of digital media, it is more important than ever before that brand impact receive consideration in safety and risk assessments. In fact, in an April 2013 report, Deloitte recommended integrating brand risk into overall risk planning, noting this as the first step in formulating a brand defense strategy10. This outlook is further bolstered by several studies that indicate a positive correlation between firm value and risk planning11. Taking just a few proactive steps in advance of an SCA event can position an organization well in the minds of all key stakeholders.

The Incalculable Cost of Not Being Prepared

While properly contemplating brand implications in risk and safety planning yields positive results, the failure to do so can also have even larger negative consequences. When something goes "horribly wrong," inadequate or inappropriate emergency response procedures can have a catastrophic and lasting impact on an enterprise. Whether this takes the form of a recorded 911 call being blasted across Twitter and Facebook, which then drives constant news channel commentary, or a critical article in a major publication criticizing an organization's failure to prepare for a foreseeable event, it can take years to recover from an incident.

Beyond the effects on brand reputation, legal ramifications for the company are also likely to ensue. Of late, the plaintiff bar has become increasingly active in circumstances involving cardiac arrest. In step with this, some recent litigation contends that AEDs should be considered an expected standard of care in sites with business traffic. This contention is based upon several factors, including heightened awareness of AED efficacy, increased AED affordability and ease of use, as well as the evolution of state-level Good Samaritan protections. Not to be overlooked among these developments is the fact that suits have been filed in jurisdictions such as Montana12 that historically have not been viewed as hotbeds of litigation.

Legal activity is not restricted to third-party claims, however. For example, late last year, a worker's compensation appeals panel in Tennessee ruled that an employee's work activities were a contributory factor in his cardiac arrest and awarded compensation to his widow13,14. More positively, from the perspective of the employer, there also have been recent court rulings upholding protections afforded under several state Good Samaritan laws15.

Although the volume of litigation to date related to cardiac event response protocols is not at the level of auto accidents and other more common events, the trends indicate that the exposure should not be ignored, particularly in light of the demographic and health characteristics of both the workforce and the customer population.

A Final Note

Every day in business, we see that the benefits of "doing the right thing" can extend well beyond inherent ethical rewards. These benefits include positive economic returns, brand loyalty (from employees and consumers), and strong word-of-mouth support for organizations. As the role of safety and loss prevention is no longer confined to reduction of losses and now also comprises an expectation of value generation, proactive preparation to guard against the impact of SCA meshes perfectly with this paradigm.

Businesses painstakingly plan for a wide spectrum of potential catastrophes, many of which present fairly low probabilities of occurrence. Nevertheless, there is inherent value in this planning and preparation because the alternative, even if unlikely, can be disaster. Given the known prevalence of SCA, prudence dictates recognizing cardiac arrest in the safety planning process. While lifesaving remains paramount, organizations should begin to view SCA protection efforts as another critical opportunity to improve employee morale and loyalty while also protecting and enhancing its brand and reputation.

References

1. Toosi, Mitra, "Labor force projections to 2020: a more slowly growing workforce," Monthly Labor Review, January 2012, p. 43-64.

2. Ogden, Cynthia L. et al., “Prevalence of Obesity in the United States, 2009 – 2010, NCHS Data Brief No. 82, January 2012.

3. Go, Alan S. et al., "Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2013 Update A Report from the American Heart Association," Circulation, Dec. 12, 2012.

4. "Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics -- 2010 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association," Circulation, 2009-121: e46-e215, p. 16.

5. All modern AEDs provide both visual and audible prompts to guide users and will not permit delivery of a shock unless the victim is in a "shockable" heart rhythm.

6. Valenzuela, Terrence D. et al., "Outcomes of Rapid Defibrillation by Security Officers after Cardiac Arrest in Casinos," New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 343, No. 17, p. 1206-1209.

7. OSHA, Best Practices Guide: Fundamentals of a Workplace First-Aid Program, OSHA 3317-06N 2006.

8. Behm, Michael, "Employee Morale: Examining the Link to Occupational Safety and Health," Professional Safety, October 2009, p. 49.

9. Lux, Elizabeth, "Brand Value: It's hard to define and difficult to manage. But companies play fast and loose with their reputations at their peril," The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 5, 2010.

10. "Using Metrics to Protect Brand Value," Deloitte Risk & Compliance Journal, April 9, 2013.

11. E.g., Itner, Chris, Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania Aon Centre for Innovation and Analytics as presented in Business Insurance May 14, 2013, webinar; Rego, Lopo L. et al., "Consumer-Based Brand Equity and Firm Risk," American Market Association Journal of Marketing, Vol. 73, November 2009, p. 47-60.

12. Bieber v. City of Billings

13. Cross v. R&R Lumber Company, Inc.

14. Worker's compensation treatment of cardiac arrest varies by state and job function.

15. E.g., Limones v. School District of Lee County, et al.; Miglino v. Bally Total Fitness of Greater New York

This article originally appeared in the November 2013 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.