Stress in the World of Industrial Hygiene: Is It Understood?

How does stress affect an employee's health to the point that we need to take it into consideration when evaluating their working environment? Should stress be included in the evaluation to management as a matter of concern?

- By Ralph Blessing

- May 01, 2019

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration currently defines industrial hygiene as "the science and art devoted to the anticipation, recognition, evaluation, and control of those environmental factors or stresses arising in or from the workplace, which may cause sickness, impaired health and well-being, or significant discomfort among workers or among the citizens of the community."

In reviewing this definition, the term "stresses" may surprise some of you as one of the things industrial hygienists are trained to deal with in the workplace.

Before we go any further, let's first discuss exactly what stress is.

Cohen (1995) did a superb job in describing stress as "a process in which environmental demands strain an organism's capacity resulting in both psychological demands as well as biological changes that could place at risk for illness." Those things that cause us stress are known as stressors, and everyone—wealthy or poor, young or old—is affected by them. Life is full of stress.

Stress can be divided into three theoretical perspectives: environmental stress, biological stress, and psychological (emotional) stress (Cohen, 1995). The environmental stress perspective is that which assesses environmental situations or experiences as they relate to adaptive demands. The biological stress perspective focuses on certain functions within the physiological systems of the body that are regulated by psychologically and physically demanding circumstances. And finally, the psychological stress perspective highlights the person’s subjective evaluation of his or her abilities to manage demands associated with situations and experiences the person may encounter.

So Why Are These Important?

As industrial hygienists, we need to understand the relationship between stress and illness, although this may be quite complex. If our employees are "stressed out," are they more susceptible to lower permissible exposure limits (PELs) of certain hazards? There are other factors that would need to be considered to manifest as an illness. These could be genetic vulnerabilities, coping styles, personality types, and support mechanisms.

As a retired Navy veteran and one of the millions of Americans who experience or have experienced stress on many levels, I was trained to evaluate the seriousness of the problem and whether I personally possessed, or could bring to bear, the resources necessary to face the problem. If my analysis deemed the problem serious and I could not cope with it, then chances were very likely I would find myself under stress (Lazarus, 1996). This would be my way of reacting to a situation that could make a difference to my overall well-being or proneness to illness; however, we must remain cognizant that not all stress is negative in nature.

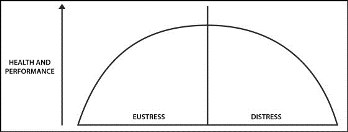

When properly trained to use the forces of stress to enhance performance, then we can look at this as being positive. Hans Selye (1956), a pioneer in stress theory, referred to positive stress as "eustress." This form of stress provides focused energy, feels thrilling, improves performance, and is perceived within the coping abilities.

This concept forces us to adjust and increase our adaptive mechanisms while advising us that a lifestyle change is justified to maintain optimal health. This same action-enhancing stress gives the special operations forces their abilities to perform almost superhuman feats while engaged with enemy forces at levels sometimes exceeding days at a time. Other eustress examples include starting a new career, getting married, having a child, or buying a new car or home.

On the other hand, stress is negative when it surpasses our capacity to cope, fatiguing body systems and causing behavioral or physical problems. This harmful stress is called distress. Distress produces confusion, performance anxiety, overreaction, and poor concentration resulting in sub-par performance. Some examples of distress include last-minute projects, death in the family, unemployment, or financial problems. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1. The Centers for Disease Control (2017) reports: one-fourth to one-third of U.S. workers report high levels of stress at work. Americans spend 8 percent more time on the job than they did 20 years ago (47 hours per week on average), and 13 percent also work a second job. Two-fifths (40 percent) of workers say that their jobs are very stressful, and more than one-fourth (26 percent) say they are "often burned out or stressed" by their work.

When Stress Becomes an Issue at Work

So how does this stress affect an employee's health to the point that we need to take it into consideration when evaluating their working environment? Should this stress be included in the evaluation to management as a matter of concern?

Chronic stress affects the body's ability to induce a prompt and effective reaction that would allow our immune system to work as required (Hafen, 1991). This concept is carried in the belief of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI), or the intricate interaction of consciousness (psycho), brain and nervous system (neuro), and the body’s defensive ability against infection and aberrant cell division (immunology) (Pelletier, 1977).

What chronic stresses could affect our employees? They could be something as simple as the day-to-day hassles of being a superintendent or project manager, being stuck in traffic, too much work for an eight-hour day, underbidding contracts, projects nearing the end of their life cycles, etc. If left unchecked, stress will suppress the immune system and could ultimately manifest as an illness.

Many psychologists have discussed the relationship of stressful situations and triggering of chronic diseases. Medd (2018) discusses research studies that indicate the following chronic illnesses can be attributed to stressful events:

- Diabetes

- Fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, multiple chemical sensitivities, and related illnesses

- Inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Parkinson’s disease

- Rheumatoid arthritis

As industrial hygienists, it is incumbent upon us to protect our employers and employees. This entails providing information and methodologies that keep the employees safe, which in turn protects the employers.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control (2017). Stress at work. Retrieved March 2, 2019, from CDC Web site: https://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/toolstemplates/entertainmented/tips/StressWork.html

2. Cohen, S., Kessler, R.C., Gordon, L.U., (1995). Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders. Measuring Stress: A guide for Health and Social Scientists. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995

3. Dombeck, Mark, Mills, Harry, Reiss, Natalie. Retrieved March 11,2019 from MentalHelp.net website: https://www.mentalhelp.net/articles/types-of-stressors-eustress-vs-distress/

4. Hafen, B.Q., Frandsen, K.J., Karren, K., Hooker, K.R., (1991). The health effects of attitudes, emotions and relationship. Provo, UT: EMS Associates

5. Lazarus, R.S., (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill., 1966

6. Medd, V., (2018). Can trauma or stress trigger onset of chronic illness? Retrieved March 1, 2019 from www.chronicillnesstraumastudies.com

7. OSHA (2019). Industrial hygiene. Retrieved February 28, 2019 from OSHA website: https://www.osha.gov/dte/library/industrial_hygiene/industrial_hygiene.html

8. Pelletier, K.R., (1977) Mind as healer, mind as slayer. New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1977

This article originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.