What Should You Stop Doing to Improve Safety Performance and Culture?

Thinking we can always be better, and hazards and risks can always be reduced, should dominate thinking throughout an organization.

What should you not do or stop doing that will improve safety performance and culture? These are difficult questions for most leadership teams to answer and agree on. There tends to be a common belief we should always do more in safety. We want to improve, so we need to do more. We had an injury or incident, so we need to do more. We want to be top-tier, so we need to do more.

Rather than always trying to do more, the goal should be to do better. More isn't always better. Better is better.

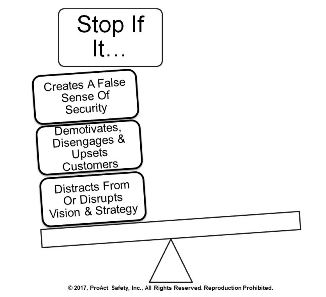

When reviewing current safety efforts with clients to determine whether they should continue, be modified, or ceased (or when pressure is felt to have a knee-jerk reaction to change direction), the following considerations and questions have been helpful to many leadership teams.

Creates False Sense of Security—Do our current efforts, or will the new effort, create a false sense of security? Traditional safety measurements (both lagging and leading indicators) often fall into this area. We haven't had as many injuries, or we have reached zero recordables. Our indicators of number of observations, audits, employee training, and perception surveys indicate we are good. Therefore, we must be safe; it won't happen to us. Maintaining a sense of vulnerability is critical in safety. Results and indicators should be recognized and celebrated, but they should also be deeply understood. Moreover, thinking we can always be better, and hazards and risks can always be reduced, should dominate thinking throughout an organization. What else might be creating a dangerous sense of overconfidence or invulnerability?

Demotivates, Disengages & Upsets Customers—Do our current efforts, or will the new effort, demotivate, disengage, and/or upset the customers of safety? A friend who works for one of the largest global corporations, known for a strong and mature safety culture, shared a story with me. He has been indoctrinated into the organization's desired way of thinking and shares their specific safety values. In other words, he gets it, lives it, and breathes it. After some significant restructuring, his office-based group decided to go off on a short get-to-know-one another, team-building exercise, and bowling was chosen. As everyone arrived at the bowling alley, prior to selecting their individual bowling balls, they were all promptly required to fill out a job safety analysis (JSA) form, immediately demotivating people who were already engaged in safety.

It is easy for safety professionals to argue the virtues and value of JSAs, but when you demotivate and disengage the very people whose engagement is critical to success in safety, you aren't winning. We must view those impacted by safety as the customers, those whose support we need to be successful in our efforts. What do your customers value, what do they need, and how will you help them see value in what you are doing to improve culture and prevent incidents and injuries? What currently takes place that demotivates or disengages people in safety?

Distracts From or Disrupts Vision and Strategy—Do our current efforts, or will the new effort, distract from or disrupt our vision and strategy? An effective strategy is a framework of choices, tradeoffs, and small bets made to determine how to create and deliver sustainable value. Your strategy should define: 1) Where you are going; 2) What success will look like in observable terms, not just results; 3) Where you are right now and where you have come from; 4) No more than a few strategic priorities aimed at both improving safety performance and culture; and 5) Measurements that provide a sense of progress and validate the priorities and efforts that support them are adding sustainable value over time. Few strategies are so perfectly defined they aren't modified during execution. Sometimes the playing field changes underneath our feet and we need to adjust, but the adjustment should come from data and not opinions. Too often, efforts in safety are developed in reaction to a single incident or injury. Instead, they should be developed by thinking strategically through where the organization needs to go and ensuring one event doesn’t distract from the safety strategy that should advance and support the business strategy.

It is almost taboo for someone to hold the belief they shouldn't try to do more to improve safety. While we should always look to improve because there is no stasis in safety, we should improve by doing things better. Accomplishing this requires a constant validation of our approaches to safety improvement. Are they helping us maintain a sense of vulnerability, motivating, engaging, and exceeding the expectations of the safety program customers? Are they adding real, sustainable value and supporting the shared vision and strategy for safety excellence? If they are not, take a hard look at your current approaches. What should you stop doing that will actually improve safety performance and culture?

This article originally appeared in the April 2017 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.