Routine Safety Audits Pay Dividends

Fork trucks were constantly driving in and out of the aisle. Fork truck traffic in the aisle and dock area was especially heavy during peak packaging runs.

- By Philip A. Leinbach, Joshua Manuel

- Jul 01, 2012

The importance of workplace safety has never been higher in U.S. manufacturing companies. Traditional performance metrics for plant managers, Quality, Delivery and Cost, are now often preceded by Safety. These metrics are reviewed in the same "Safety First" priority order during work cell “huddles” prior to shift start. Many companies have mandatory safety orientations for visitors and contractors before they can enter or work in a factory. Some companies begin every meeting with a safety moment by the meeting organizer to keep personal safety first and foremost in people's minds. Environmental, Health & Safety departments institute safety processes, train employees, and monitor compliance. These practices reflect companies' common desire to build and maintain cultures that value personal safety.

Despite these pervasive and persistent efforts, unsafe practices that could lead to an accident still happen. Examples of workplace risk are found every day by OSHA inspectors. A serious violation is defined as one where a substantial probability that death or serious physical harm could result from a hazard about which the employer knew or should have known. A brief list of serious violations culled from recent OSHA citations covers machine guarding; powered industrial trucks; fall, struck-by and crushing hazards; chemical exposure; and energy lockout. Constant vigilance is a necessity.

How can workplaces become even safer? What else can be done?

Continuous improvement in safety performance through prevention is achieved in two basic ways. The first approach involves redesigning equipment and work environments to eliminate risks. Light curtains, dual palm buttons, lift assists, fume extractors, and mist collectors are examples of technology that reduces or eliminates the possibility of injury. These and other solutions have been adopted successfully throughout numerous industries. When failsafe technology solutions are either unavailable or unaffordable, the second approach comes into play: Safe Operating Procedures. Procedural-based safety requires all workers to comply with the written instructions for safely performing a task (e.g., entering confined spaces, performing hot work, removing parts stuck in a machine, driving a fork truck). This class of solutions relies on people doing the right thing each and every time, which has proven to be a significant challenge. The best procedures in the world will not achieve the intended results if workers ignore them.

Rather than wait for non-compliant behavior to manifest itself in an injury, companies monitor worker compliance with existing safe operating procedures. Supervisors routinely observe employees as they work to determine if intervention is needed to ensure compliance. In addition to front-line supervisor responsibility, companies will often have a safety department representative or other management personnel perform internal audits for an additional layer of preventive control. The results of such oversight can indicate whether corrective actions need to be focused on improving a process or solely an individual's behavior.

Is that as good as it gets? We will now present a real-world example in which the aforementioned preventive actions are taken one step further. By employing an external audit of safe operating practices, a company gained new perspectives on how well its safety management systems were functioning.

An Illustration

A leading U.S. manufacturing company knew it had a congestion problem in one of its high-volume packaging buildings. One aisle served an automated palletizer, two automated stretch-wrapper systems and some manual packaging stations. All of these operations were located next to the shipping docks, so fork trucks were constantly driving in and out of the aisle. Fork truck traffic in the aisle and dock area was especially heavy during peak packaging runs. In addition to fork truck drivers, the work area was staffed with operators who performed manual pack operations and cleared container jams in the packaging equipment and conveyors. There was a continual interchange of fork trucks and operators. This interchange posed fork truck/pedestrian hazards that the company wanted to eliminate.

The proposed solution had already been designed: replace manual packaging with automated equipment and provide more workspace. The company simply needed to justify expenditures on equipment and floor space by quantifying the hazard that existed. They proposed doing so by contracting a third party to assess safety hazards in the area.

The proposed solution had already been designed: replace manual packaging with automated equipment and provide more workspace. The company simply needed to justify expenditures on equipment and floor space by quantifying the hazard that existed. They proposed doing so by contracting a third party to assess safety hazards in the area.

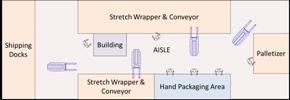

The company selected an engineering consulting firm, to perform an independent safety assessment. Prior to initiating the audit, the company's representatives described the types of unsafe activities that the independent safety auditor would likely observe. The study team defined two categories of unsafe activities: (1) Fork truck/pedestrian actions that were in violation of the safety rules regarding fork truck and pedestrian interaction, and (2) Behavioral actions by workers that demonstrated either negligence of the rules or blatant disregard for safety. The auditor conducted a 24-hour audit of the packaging area over a 36-hour period to obtain a representative sample of actual operating conditions for every hour of the day. Figure 1 illustrates the area studied and how lift trucks and workers perform their duties in close proximity to one another. During the course of the study, the consulting auditor documented every "near miss" and safety concern, when it occurred, where it occurred and whether the person(s) involved were associates or contract workers.

The results confirmed that fork truck/pedestrian hazards were, unfortunately, plentiful. Fork trucks travel everywhere in the area, and no place was immune to the potential for fork truck/pedestrian hazards. There were 44 observed instances of fork truck/pedestrian "near misses" during the 24-hour study period. Specific observations included pedestrians' not making eye contact with fork truck drivers before walking behind the fork truck, fork truck drivers moving loads while pedestrians were still packing boxes, and two fork trucks almost striking each other. Each "near miss" was charted on a map of the area (Figure 2) to portray visually where it occurred.

The results confirmed that fork truck/pedestrian hazards were, unfortunately, plentiful. Fork trucks travel everywhere in the area, and no place was immune to the potential for fork truck/pedestrian hazards. There were 44 observed instances of fork truck/pedestrian "near misses" during the 24-hour study period. Specific observations included pedestrians' not making eye contact with fork truck drivers before walking behind the fork truck, fork truck drivers moving loads while pedestrians were still packing boxes, and two fork trucks almost striking each other. Each "near miss" was charted on a map of the area (Figure 2) to portray visually where it occurred.

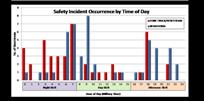

The audit results also revealed some potential safety concerns that had not been on the company's radar. Behaviors such as not following lockout/tagout guidelines, walking across moving conveyors, and throwing packaged boxes are a few examples of the 49 recorded behavioral near misses. Figure 3 shows there were just as many behavioral concerns that had previously gone unnoticed as the fork truck/pedestrian near misses that were expected. The data in Figure 3 also show a decline in the number of overall safety incidents during hours when management team members typically are on the floor to observe work activities, an indication management and associates were not sharing the same safety values.

The client concluded from this data that the safety culture had to be improved at its core from one that is controlled by management to one that is owned by everyone.

The client concluded from this data that the safety culture had to be improved at its core from one that is controlled by management to one that is owned by everyone.

The audit results enabled the company to justify its request for funding the capital improvements they were seeking--their original goal. More important for the company, however, the study also elevated the significance of improving their safety culture. Members of the management team quickly responded to extinguish "near misses" and educate their workforce on safe working behaviors. Policy changes were promptly updated to enhance the vision of their safety program. The company should be commended for its positive response and "let's fix it" mentality.

Implications for Management and Staff

There is no denying that American industry has taken major strides toward improving workers' safety and continues to do so. Consider these commonplace aspects of a safety culture:

- Required training programs to heighten awareness of safety risks and educate employees on safe work practices

- Documented safe operating procedures

- Internal safety representatives and supervisors monitor behaviors and provide feedback

- Suggestion systems to improve safety

- Track safety performance with key high-visibility metrics

Despite all of these actions designed to prevent injury, accidents still happen. In some cases, the system may fail to anticipate a situation, so a safety gap exists. Structural gaps of this kind must be closed through appropriate corrective actions (e.g., new technology, new procedures, new training) that will make the safety system even more reliable in preventing accidents. When accidents occur because individuals knowingly expose themselves and others to unnecessary risks, the remedy must reside outside the safety system in the human resource processes that deal with ensuring adherence to work behavior standards. After a company has done all it can reasonably do to create a safe working environment, the employee must assume personal responsibility for complying with all safe operating practices. Consequences for willful non-compliance must be real.

Workplace safety improvement begins with knowing what workers are actually doing. Which behaviors are compliant with existing safety standards and which behaviors pose potential hazards? An independent safety audit can play a beneficial role in assessing workplace safety and thereby help a company take its safety culture another step higher. An independent audit offers the following benefits:

- Provides fresh perspective by trained, neutral observer

- Spans all working hours for comprehensive evaluation

- Pinpoints specific aspects of safety system to improve

- Reinforces the company's safety commitment to the workforce

Many seemingly healthy people visit their doctor for an annual physical examination to detect early warning signs. In addition to checking heart rate, blood pressure, and running tests on blood samples, the doctor asks about behaviors that pose a risk to your health. If there is a problem, the patient wants to know early because it is almost always easier to overcome problems when they are small.

The same philosophy can apply to a company's safety culture. A routine safety audit by an independent auditor may reveal that all systems are working as they should. That is what we hope to find. On the other hand, what if disturbing clues are detected? Recognizing the presence of a potential problem is the first step in resolving it. The time to address such concerns is ASAP because it is much better to be safe than sorry.

This article originally appeared in the July 2012 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.