Page 3 of 5

Improving Personal Risk Assessments

This article is excerpted from the book “Inside-Out: Rethinking Traditional Safety Management Paradigms,” by Larry Wilson and Gary Higbee.

Gary and I had been talking about adding human factors such as rushing, frustration, fatigue, complacency and critical errors (there are four critical errors: eyes not on task, mind not on task, line-of-fire, and balance, traction, grip) to the existing components of a safety management system, such as near-miss reporting, job safety analysis, and incident investigation. We had data from companies showing a marked increase in near-miss reports that correlated with significant injury reductions, and we agreed this was also the best place for most companies to start, in terms of integrating human factors and critical error reduction techniques into their safety management system.

"The only thing I'd add," Gary said, "is that when we got all of these near-misses -- and it was a huge increase -- you make sure you get the things, the physical things, taken care of. You see, most of these 'new' near-misses will be personal -- like someone running down the stairs and losing their balance -- but if something was wrong with the handrail or it's loose, don't just recommend 'self-triggering' on the rushing. Make sure you get the handrail fixed, too."

I just nodded my head. Gary was such a traditionalist. "Okay, so near-miss reporting is probably the first thing you'd want to do," I said. "What next?"

"Well, the next proactive approach is to look at a couple of systems that we're all familiar with. Most organizations have JSAs or JHAs, and some actually do something that's a little bit more complicated, which is a risk assessment. But rarely, if ever, do we see any human factors in those JHAs or JSAs or the risk assessment. They were all looking at compliance or physical hazards or quantifiable risks. But sometimes the system forces or directs or encourages employees to do certain things that increase the risk. And the JSA is supposed to help us look at all parts of the system step by step, every step that a person does on a job, every step that a group of people do on a job. And by going through it step by step and by writing down 'the potential for injury that we have in each one of these steps,' and then writing down 'this is the corrective action' or 'preventative measures' taken for each one of those potential injuries, the idea is that, hopefully, by going through this process step by step, we don't miss anything.

"The problem is that the human factors aren't in there at all. And yet the reality of the situation is that some jobs lend themselves to creating the need -- at least a perceived need -- to rush. Certain things allow us or encourage employees to be in one of the states or make one of the four critical errors. And that is hardly ever included in a JSA."

As Gary was talking, I started thinking that some jobs by their very nature have these states built in to them. For instance, you get a flat tire on the freeway. This is not something that you planned, it is going to cause delays, there's a certain amount of effort that you would prefer not to make -- getting the tire out of the trunk and everything else -- and there's also expense that goes along with this. So there are jobs where you could anticipate frustration coming into the job or developing during the job if it wasn't going well, and there are also things like a flat tire where you could anticipate frustration and rushing before the job even starts because of the nature of what it is that you're having to fix.

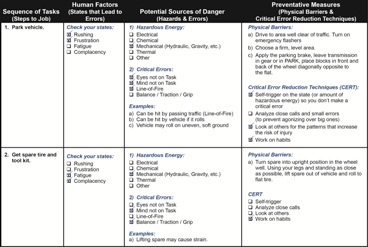

Gary continued on about the JSAs. "Okay, so what we would encourage the safety folks to do is to add a fourth column to the JSA. And as you can see in Figure 1, we've put the four states (rushing, frustration, fatigue, complacency) in the second column and the four critical errors in the third column. We’ve also put the four critical error reduction techniques in the fourth column. The methodology is the same as before, only with each step, look at the second column for rushing, frustration, fatigue and complacency being factors; then, in the third column, identify which critical errors the state or states could potentially cause, and then look at the critical error reduction techniques in the fourth column that would help to prevent an incident or accidental injury if a critical error was made. Note: This also should help with ensuring that safety barriers and safeguards are not missed or forgotten.

"Now, most safety professionals know that you probably should have had the employees doing the JSAs originally. But it's critical at this point, because now we want to know what risks are involved with rushing, frustration, fatigue, and complacency, and they're the only ones who know what really happens on that job or on that task where these come into play. So what we're trying to do is help them do a better job of assessing risk. They're the ones who do it; they know what's happened in the past; and now we're giving them a tool to assess all the risks with a job and assist in that change so they can start doing risk assessments from more than one perspective. Really from the inside out."

I told Gary that I would hear this over and over again from safety professionals lamenting about hazard recognition and risk assessment: how their employees don't recognize, can't recognize hazards, and they can't do a proper risk assessment. And they would, of course, be trying to develop tools, such as risk matrixes, to help their employees evaluate risk. But if you look at these risk assessment tools, all of the risks they evaluate are external. Evaluating the environment, evaluating the hazard, and trying to give them helpful tools to quantify the risk -- when these tools, in my opinion, were flawed right from the very beginning because they were missing the most important piece. The risk, in terms of primary causation, is rarely the equipment breaking or failing, and in the workplace -- maybe not so much on the highway -- in the workplace, it's rarely the other guy doing something unexpectedly, either. The main risk is the person doing something unexpectedly themselves, like making a mistake. And people don't evaluate that kind of risk very well or very readily.

Question: What has More Risk?

- Driving 100 mph, focused on road

- Driving 60 mph, not paying attention

I can think of a personal example years back when we were over at the mother-in-law's for Thanksgiving dinner. It's the huge turkey spread, and while we're eating dinner, it starts snowing. My mother-in-law is telling me that we shouldn't drive home, we should stay the night. I'm looking out the window at how much it's snowing and saying, "Oh, I don't know if it's really that bad...." We're checking the Internet. We're looking at the weather reports. We even turned on the radio to hear anything about the highway being closed. All kinds of physical assessments on the risk.

None of us, including me -- until we're at about the third hour of the drive home, and I am so tired I can barely keep my eyes open -- thought, "What is the risk of driving three hours after a big turkey dinner and falling asleep at the wheel?" We didn't think about that at all.

And yet people falling asleep at the wheel represents approximately 25 percent of the fatal car cashes in Canada and the United States. But there's a natural tendency for people to look at that physical environment, those physical hazards, when they're doing a risk assessment and not looking at "What are my states of mind?" "How complacent have I become with this activity?" These are rarely questions that people get involved with in terms of risk assessments. And yet complacency is a contributing factor (major or minor) with almost every accidental acute injury.

If you start asking people, "Can you think of a time you've been hurt -- other than sports -- when you were thinking about what you were doing and the risk of what you were doing at the exact instant when you got hurt?" You will rarely have more than one hand in the air, if you have a hundred people in front of you. Maybe once in a while two hands in the air, and that's for their whole lives. So complacency is a huge contributing factor, but it's not the kind of thing very many people take into account when they're doing risk assessments or discussing a job safety analysis. It’s not like you hear, "Okay, you guys have been doing this for 15 years, so let's discuss the problems complacency might cause" at very many tailboard meetings or toolbox sessions. You're much more likely to hear about the hazards, rules, and procedures.

Those Little Mistakes

A few years back, I attended a big petroleum conference. I was the opening keynote speaker and did not have to leave until the next day, so I stayed to hear the closing keynote speaker. He was a very interesting guy, a surfer dude named Bruce, who actually had a wind surfer strapped to the roof of his 4x4. I talked with him afterward. He's an outdoor adventurer; his real job, if you will, is a whitewater rafting guide on the Yukon River. But he's gone whitewater rafting in the Blue Nile River and the Amazon. He's gone across the Sahara desert on camels. He has climbed Mount Everest. He's climbed a number of peaks in the Rocky Mountains, and he and one of his close friends have done a number of first ascents skiing down some of these peaks in the Rocky Mountains. And the guy has got phenomenal, just phenomenal, video and still pictures of these adventures. Much of his presentation was just this incredible visual.

We were seeing videotape that gave you the feel for what it's like being at the peak of Mount Everest or on the Blue Nile or the Amazon. It was just amazing, and he's showing us the people on the different excursions: here are the Sherpas, here's their family, he's showing us all the people involved in all of these treks. And then he starts talking about the risks, which aren't obvious to all of us watching the video. When you're climbing the top of Mount Everest, it's almost minus 30 Celsius up there; you can't see it in the videos, but he's talking about it. He’s also talking about the thin air, and you can see how slowly everybody is moving. So you get a bit of a visual representation of the low oxygen.

He talks about how the people in their parties are always, continuously, doing risk assessments. Monitoring the weather, looking at the weather, making sure they're not going to get caught in a storm because that could be deadly. Looking at the equipment, inspecting and assessing the equipment. The risk is obvious if the rope breaks or if the D ring fails. So they are continually monitoring the obvious things. "But rarely," he says, "did I find people assessing risk in terms of themselves on a personal basis." They didn't ask questions like, "What if I make a mistake?" "What if I sprain an ankle and can't walk?" Carrying someone is too hard at that altitude, so he explained that a sprained ankle or a blown knee could be a death sentence. And he's going through all of these little mistakes that people can make. He tells us a story about how one time he nearly forgot the GPS and the satellite radio phone at the camp site because he didn't do the double-check before they left. He was pretty sure he had it, but he didn’t. Those little mistakes that complacency can cause.

At the end of his presentation, he starts showing us pictures of some of the people who were with him on these excursions. Then, he shows us their grave site, or in some cases, the makeshift grave sites they made for them on the mountain.

"All of these people died," he says, "because of the little mistakes that complacency can cause in these environments." He concludes that his take on risk assessment is that more than 80 percent of the risks in these extreme environments where he was going were not the weather, not the equipment, not the other people out there on the expedition with you. It was you, and it was the simple mistakes that complacency can cause. More than 80 percent of the risk was with yourself, he says, but rarely, if ever, did people take that into account when doing risk assessments.

It was a very powerful presentation, especially the way he introduced all these people and their families and then showed you their tombstones or makeshift grave sites.

Later on, I ran into him in the parking lot. He was parked two cars away. We talked about the four states, not just complacency, and the four errors. I briefly explained the four critical error reduction techniques. Then we talked about the three sources of the unexpected, and I said what I had found -- and at this stage of the game, we have asked more than 100,000 people -- is that the risk in the self-area, in terms of what actually initiated that chain reaction, was well above 95 percent. And he said, "I don't have any data on the 80 percent. All I know is that it's really high, and I wanted people to realize that it was really high. I just picked 80 percent because I wanted them to realize that when they do risk assessments, they've got to look at themselves."

We talked for a few minutes more. I told him the presentation was great, we exchanged business cards, and we parted company. But I never forgot the presentation. With his surfer dude casual demeanor and humor, you never expected to see those tombstones. It was the classic sucker punch.

Looking at Risk from Two Perspectives

Getting your employees involved with redoing your JSAs so they include human factors and critical errors will do more than just ensure that these concepts don’t fade away or become the flavor of the month. By getting your employees involved with this, you’re going to start the wheels moving in terms of how they assess risk in the future, before starting a new job.

Now they'll look at risk from two perspectives: from the outside in and from the inside out. But more importantly, this process also helps teach them to be able to monitor their level of rushing, frustration, fatigue, and complacency when they're doing any job and to be conscious of changes in those states as being a risk, as well -- as much of a risk as changes in the environment or with the hazards. And that is so much more powerful than simply being able to rewrite the procedures so this stuff doesn't fade away.

This article originally appeared in the October 2011 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.