They Like It Hot

Smokejumpers battle wildland fires to protect lives and property. There’s no shortage of applicants.

- By Marc Barrera

- Dec 01, 2008

Firefighting is one of the world’s most dangerous and highly regarded jobs. As kids, many of us want to be firefighters when we grow up—but few of us actually do it. For Larry Wilson, his respect for the job was motivation enough not only to become a wildland firefighter while in college, but also to take it a step further and become a smokejumper.

Firefighting is one of the world’s most dangerous and highly regarded jobs. As kids, many of us want to be firefighters when we grow up—but few of us actually do it. For Larry Wilson, his respect for the job was motivation enough not only to become a wildland firefighter while in college, but also to take it a step further and become a smokejumper.

“I was working in the Gila National Forest in southern New Mexico, and they have a detail of smokejumpers that would come down every year,” he explained. “So I worked on fires with them. I was impressed with the professionalism and experience level of those guys.” Wilson is now a training officer at the McCall Smokejumper base in Idaho. He stresses smokejumping is not for entry-level firefighters; rather, they are a group of experienced wildland firefighters who specialize in making the initial attack. The proof is in the training.

Competition is fierce among wildland firefighters to become one of the estimated 400 smokejumpers in the United States. “Every year, each base receives hundreds of applications for anywhere from six to 12 positions,” Wilson said. “The hundreds of applications that are received are qualified applicants, so it is a very keen competition.” Once accepted, the newcomers undergo five weeks of intense, specialized training.

“One of the things that they can do to really prepare themselves for it is to show up in the best shape of their life, in excellent physical condition, because it is physically demanding,” Wilson said. “There is a lot of physical stress that’s put on people, and that’s something that you can’t prepare for overnight.”

Although the trainees already are experienced, highly trained wildland firefighters, smokejumper training helps to refresh their firefighting skills as they learn the many new skills necessary for the job, including aircraft exiting, parachute maneuvering, proper landing, and tree climbing. “If they land in trees, since we jump timbered country and rough terrain, we teach them how to rappel to the ground and to retrieve the para cargo or the parachute if things are in the trees,” said Wilson.

Engaging the Fire

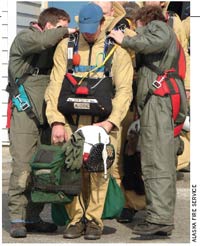

Once the training is complete, safety continues to be the highest priority for any smokejumping team. Numerous checklists and standard operating procedures follow a call to action; as the aircraft goes through its safety checks, a smokejumper suits up and performs at least one “buddy check” on another team member’s gear.

Once in the air, the most experienced smokejumper in the team assesses the fire, and a safe jump zone is determined. “An experienced smokejumper that has gone through some additional training is identified as a mission coordinator—we call them spotters—and they size up the fire from the air and identify who will be the incident commander, or the jumper in charge,” Wilson said. On the ground, smokejumpers get out of their padded, Nomex-coated Kevlar jump suits, stow their parachutes, grab their personal gear bag (the PGB contains items such as hard hats, gloves, and a fire shelter), and retrieve any para cargo that is dropped. This cargo typically contains water, food, sleeping bags, and tools the smokejumpers may need, such as FEDCO pumps, backpack pumps, fusees, shovels, pulaski axes, McCloud rakes, and more.

Once the team is situated, the members focus on assessing the fire and then anchoring and flanking it, Wilson said. First priority is given to establishing safety zones and escape routes. “Normally we’ll scout the fire, give a briefing to the crew, and come up with a plan to engage the fire,” he said. “So, basically you find the heel of the fire, a place where it’s already burned, and you start from there: You anchor it. You follow a flank by digging what we call a fire line, separating the fields down to mineral soil, and basically digging a trail along the fire and proceeding along the flight of the fire until you pinch the head.”

Hazards encountered while trying to accomplish this task can include rolling rocks and burning snags—dead trees—that can topple onto smokejumpers or throw embers across the fire line. To help mitigate these hazards, an experienced smokejumper is always posted on high ground to watch the fire, charged with assessing the situation and keeping the team out of danger while ensuring the fire is put out safely.

“There are definitely hazards out there, and a risk assessment is done, but really what’s done is more risk management,” Wilson said. “It’s a process that’s really different from the risk assessment, and one of the things is gathering information as much as you can about the fire, what the fire’s going to do, what the hazards are— identifying those and recognizing them, and then trying to mitigate those so you don’t have those injuries.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2008 issue of Occupational Health & Safety.