Chronic Venous Insufficiency and Chronic Venous Disease in Workers Standing or Sitting for a Prolonged Time Period

Workers who stand on their feet for an extended amount of time may be at risk for health issues.

- By Bernard Fontaine

- Sep 27, 2022

The National Retail Federation forecasted that retailers and merchants hire between 730,000 and 790,000 seasonal workers during the holiday season. Many workers have little, if any, opportunity to sit during their work shift. Increasingly, workers across a variety of occupations are required to stand for long periods of time without being able to walk or sit during their work shift. The basic physiological change that occurs in the body during prolonged standing or sudden standing from the supine position is that there will be increased pooling of blood in leg, which decreases the venous return resulting in a decreased cardiac output, which ultimately causes systolic blood pressure to fall (hypotension).

For example, in operating rooms, nurses and doctors must stand for many hours during surgical procedures. Other people with jobs that require them to primarily stand without the ability to sit down include a wide variety of professions. These include retail sales clerks, cooks, bank tellers, waiters, teachers, shop and warehouse workers, ticket agents, cashiers, machine operators, food processors, agricultural harvesters, train engineers, security personnel, construction workers, printers, casino and hospitality workers and production and assembly line workers. It is estimated that nearly half of workers worldwide spend more than 75 percent of their workday on their feet.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) conducted a review of the literature to examine the risks of prolonged standing in the workplace. “Evidence of Health Risks Associated with Prolonged Standing at Work and Intervention Effectiveness” was published in Rehabilitation Nursing in 2014. While standing is natural, when it is a regular part of many job assignments, more often it is done for an extended time period without rest. Workers frequently complain of lower back and lumbar pain besides sore feet, swelling in the lower legs and ankles and varicose veins.

Based on the research reviewed, there appears to be ample evidence that prolonged standing in the work place leads to a number of negative health outcomes. The studies consistently reported increased reports of physical fatigue, muscle pain, leg swelling, tiredness and discomfort from prolonged standing. Also, there is significant evidence that prolonged standing also increases risk of low back pain, cardiovascular problems and pregnancy outcomes.

A reliable characterization of prolonged standing is defined as a workday where workers are required to continuously stand for eight hours per day. Various groups, such as the Association for Peri-Operative Registered Nurses (AORN) and Dutch researchers, have suggested time limits for prolonged standing, which they believe would be effective. Perhaps the solution can be found in how work is done. Jobs should be designed to allow the employee to have control over their own bodies, such that they are able to assume different sit/stand postures and move as they need throughout their work shift.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines standing when workers are not sitting or lying down. Standing includes work activities like:

- Walking such as tellers who walk to escort customers to a safety deposit box.

- Climbing such as electricians climbing ladders to reach wires placed in ceilings.

- Low posture such as stooping, crawling, kneeling, and crouching like pest control workers,

- Workers who stand their entire shift except during paid breaks.

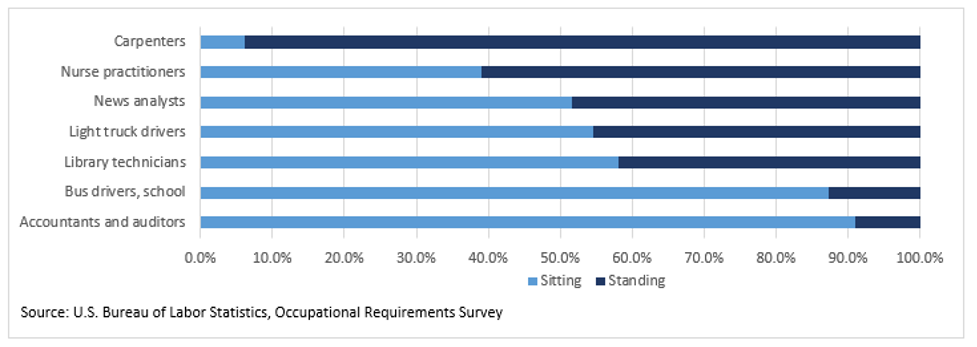

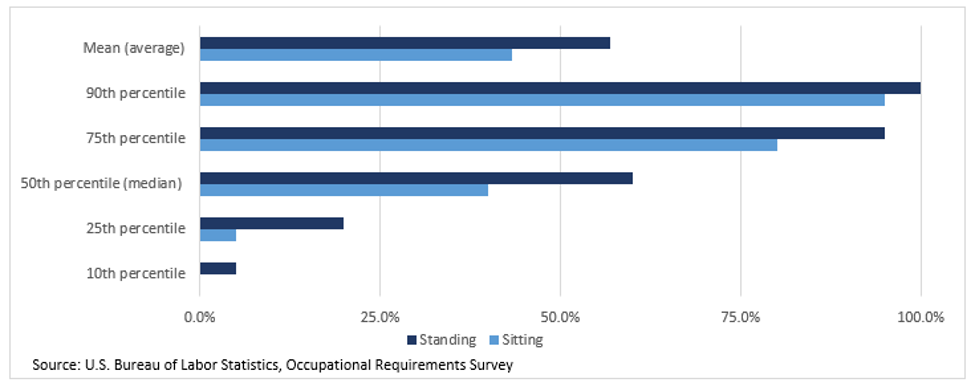

On average, nurse practitioners studied were required to stand for 61 percent of the workday, while school bus drivers were required to stand for 12.7% of the workday. According to the BLS 2021 Occupational Requirement Survey (ORS), on average civilian workers spent 43.2 percent of the workday sitting and 56.8% standing. Percentile estimates provide a range of requirements among workers. For example, at the 10th percentile, workers were required to stand for 5.0 percent of the workday while at the 90th percentile, workers stood for 100.0% of the workday. At the 50th percentile (median), 50% of civilian workers spent 60% or less of the workday standing and 50 percent of workers spent 60 percent or more of the workday standing.1

Figure 1 – Percentage of Workday Required to Stand by Occupation – 2021

Figure 2 – Percentage of Workday Required to Sit or Stand

Epidemiology of CVI and CVD

In a 2007 paper published by Shemesh et al., the authors presented a theory about mechanical hydrostatic pressure generated by long periods of standing at the workplace is a major etiologic factor in developing Chronic Venous Insufficiency (CVI) in the legs. CVI is an occupational health problem that affects about 50 percent of the working population in western industrialized countries. A recent study evaluated the etiology and prevalence of Chronic Venous Disease (CVD) of the lower limb in workers, and to identify some risk factors using a detailed and systematic analysis of the literature from 1964 to 2011. There is an important relationship between standing position at work, CVI and CVD. The prolonged orthostatic position of the body implies venostasis, high pressure and risks of blood clots and thrombosis. While standing, workers can produce Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) of chemicals that affects cell membranes that cause endothelial damage and increased in vascular permeability in the affected legs.

Other risk factors investigated include sitting during work time, weight lifting-moving and exposure to heat sources but these risk factors are less important than orthostatic body position. Age, sex and familiarity were relevant as the extra-occupational risk factors. A more accurate exposure risk assessment considered the role and prolonged orthostatic position on the development of venous disease in the lower limb, the role and the length of standing time both at work, recreation and at home. Also there should be a universal definition of what constitutes prolonged standing that includes correct standing posture and position (i.e. within 1 m2 or steps) and time of exposure (i.e. one hour or 50 percent to 70 percent of work time).

The issue of working conditions and the health ramifications were reviewed in Israel with special emphasis on occupations requiring prolonged standing. Researchers discussed the physiological and medical aspects of prolonged standing in the workplace. Searching the literature, 19 studies were found which specifically examined the effect of prolonged standing versus prolonged sitting at work. Most of these studies suggested that prolonged standing may result in the developing and aggravation of CIV. The association between prolonged standing and venous insufficiency was found to be more pronounced in women than in men.2

Prolonged standing at work has been shown to be associated with a number of potentially serious health outcomes, such as lower back and leg pain, cardiovascular problems, fatigue, discomfort and pregnancy-related health outcomes. Recent studies examined the relationship between these health outcomes and the amount of time spent standing while on the job. A review of the health risks suggests a need for medical and ergonomic interventions for those workers involved in occupations requiring prolonged standing.

Data on the prevalence of CVI disorders between 2006 and 2015 in Germany are scarce. A population-based observational study was based on clinical exams, personal history, and medical examinations. Descriptive data analysis was done to determine the prevalence of both CVD and CVI and the occurrence of potential risk factors. Chi-squared tests were performed to estimate the influence of these risk factors of CVD. Other reported comorbidity risk factors include:

- Diabetes,

- High levels of fats in the blood (hyperlipidemia), such as cholesterol and triglycerides,

- Smoking,

- High blood pressure,

- Obesity,

- Lack of exercise and

- Diet high in saturated fat

In total, 19,104 employees from different branches were included in this study. The majority of the examined people were doing office work (n = 8157; 80.2 percent). A total of 4038 persons (21.1 percent) shows at least one sign of CVD. At least one sign of CVI could be found in 679 persons (3.6 percent). Being female was found to be protective with an odds ratio of 0.66 (95 percent CI 0.59-0.73). Overall, there was a clear indication for active venous treatment in 22.3 percent of adult workers in Germany.3

The prevalence of CVI was investigated in 44,777 unselected primary care outpatient clinics in 17 of the 20 districts in Portugal (1993). The diagnosis of CVI was established clinically by 427 participating general practitioners. CVI appeared to be more prevalent in females, with a female to male ratio of 2.1:1. The disease affects all age groups, but in females its prevalence increases sharply after 15 and 20 years, while in males became important about 10 years later. The maximum age-specific prevalence was reached between 55 and 64 years in both sexes, when CVI is present in 58 percent of females and in 35 percent of males. Overall prevalence of CVI was calculated using the 1991 data from a population census by direct standardization method. The estimated prevalence of CVI in males was 17.8 percent and in females was 34.1 percent.4

Another cross sectional study looked at the prevalence and risk factors of CVI in a South European occupational population. Over a seven-month period a questionnaire of symptoms, general data and life style habits was administrated to 1,604 consecutive females (73.3 percent) and 586 consecutive males (26.7 percent). A clinical examination was later performed to evaluate the condition. Subjects were classified into four (4) groups: asymptomatic, light, moderate and severe CVI. Univariate and multivariate analysis were used in the analysis.

The prevalence of CVI all classes confounded was 51.4 percent (62.3 percent in women and 21.8percent in men); the prevalence of moderate and severe CVI was 10.4 percent (12.1 percent in female and 6.3 percent in male). Age Odds Ratio (OR): 1.93, 95 percent confidence interval (CI): 1.55-3.53), female sex (OR: 2.34, 95 percent CI: 1.62-2.30), obesity (kg/m(2)) (OR:1.11, 95 percent CI: 1.07-1.15) and familial history of CVI (OR: 2.80, 95 percent CI: 2.02-3.89) were risks factors of moderate and severe CVI. The comparative analysis extended to other risk factors: history of leg injury, pregnancy; a sitting posture at work.5 There are multiple stages of Chronic Venous Disease (CVD).

CVI in occupational populations is often poorly recognized at work. The magnitude of the problem has never been thoroughly investigated around the world. A study in the Netherland looked at the epidemiology and risk factors of CVI in males with a standing position at work. A simple diagnostic instrument was developed to screen for CVI. A total of 387 male workers with a standing profession were examined by a questionnaire, physical examination, Doppler ultrasound, light reflection rheography and optical leg volume.

The results showed that CVI was present in 29% of workers and correlated with age, weight and duration of standing work. Complaints of the legs were reported by 81 percent of the individuals with CVI but also by 63 percent of the persons without CVI. The questionnaire had a predictive value of 80 percent in detecting CVI. Neither the questionnaire nor other investigative measures proved to be efficient in diagnosing CVI by physical examination in combination with Doppler ultrasound investigation.6

Interventions and Strategies

So what can an employer do? There are numerous interventions such as floor mats, shoe inserts, adjustable chairs, sit–stand workstations and compression stockings that can be used to reduce the pain, discomfort and fatigue from prolonged standing. In reviewing the studies examining the effectiveness of interventions, it was concluded that dynamic movement appeared to be the best solution for reducing risk of these health problems due to prolonged standing.

The ability for workers to “have movement” during work, such as walking around, or being able to easily shift from standing to sitting or leaning posture during the work shift seemed to be a common suggestion in nearly all of the literature. Other interventions include more break or extended periods with comfortable seating and reduce the amount of time spent standing or walking. Install rubber floor mats and provide adjustable tables or work benches to allow the worker to sit or stand while performing their work. Changes in footwear comfort or arch supports should be considered for those workers who must stand or walk as part of their job.

There are few exercises workers can do to help stay comfortable while standing for long periods of time. These include bending the knees slightly periodically to provide a more natural posture and lifting the heals and toes of the shoe to help strengthen the legs while standing. From an ergonomic viewpoint, workers can rest on foot on a stool while standing to provide some relief to the lower back. While standing in place, the worker can raise or kick one leg behind them when their legs become tired. Another exercise that may be helpful to stretch the hips by putting one foot up on a chair or a stool and lean forward to stretch your upper thigh and hips, then switch sides. Another remedy is a foot and calf massager or using a percussion gun are very common for deep tissue massage. Compression stockings can be worn help circulate the blood in the legs and feet. Put these stockings on before standing for a long time improved blood flow and reduce swelling in the legs. Medical intervention strategies should be considered for workers along with controlling other risk factors such as diabetes, cholesterol, triglycerides and saturated fat in the diet, smoking, obesity and exercise.

Conclusions

Occupational health and safety professionals should consider the human factors and ergonomic impact for those workers who need to stand for most of the workday. A work site evaluation should include a questionnaire and an interview of workers who report injury, illness, disability or disease related to prolonged standing. Medical opinions should be obtained from healthcare providers when there are complaints or evidence of varicose veins, poor circulation and swelling in the feet and legs, foot problems, joint damage, heart and circulatory problems and pregnancy difficulties. or reported comorbidities such as obesity, smoking or cardiovascular or pulmonary disease.

Workplace interventions should be carefully reviewed to reduce the time standing by using either engineering or administrative controls along with the selection and use of personal protective equipment. Simple job or workstation design can make it possible to reduce the requirement to stand. Some workers may be reluctant to use seats because they fear this will be interpreted as a sign of laziness by managers or rudeness by customers. In the United Kingdom, researchers reported that workers in lower status jobs are far more likely to be required to stand for long periods. Workers in higher status jobs are much less likely to be required to stand for long periods without access to a chair or rest. CVI and CVD are clearly unreported occupational illness and disease that can be better managed and controlled with a proper exposure risk assessment and implementation of cost-effective mitigating interventions.

There is sufficient evidence to conclude that prolonged standing does have a negative impact on worker health. Leg swelling, fatigue, tiredness, muscle pain, body part discomfort and lower back pain are some of the issues faced by people who stand excessively due to their work routine. By identifying the hazard and controlling the risk, workers can be more productive and perform better.

References:

- S. Bureau of Statistics - Occupational Requirements Survey Job Related Information– Standing and Sitting https://www.bls.gov/ors/factsheet/sit-and-stand.htm

- Shai A, Karakis I, Shemesh D. [Possible ramifications of prolonged standing at the workplace and its association with the development of chronic venous insufficiency]. Harefuah. 2007 Sep;146(9):677-85, 734.

- Kirsten N, Mohr N, Gensel F, Alhumam A, Bruning G, Augustin M. Population-Based Epidemiologic Study in Venous Diseases in Germany - Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Medical Needs in a Cohort of 19,104 Workers. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2021 Oct 29;17:679-687.

- Capitão LM, Menezes JD, Gouveia-Oliveira A. Epidemiologia da insuficiencia venosa crónica em Portugal [The epidemiology of chronic venous insufficiency in Portugal]. Acta Med Port. 1995 Sep;8(9):485-91.

- Lacroix P, Aboyans V, Preux PM, Houlès MB, Laskar M. Epidemiology of venous insufficiency in an occupational population. Int Angiol. 2003 Jun;22(2):172-6.

- Krijnen RM, de Boer EM, Adèr HJ, Bruynzeel DP. Venous insufficiency in male workers with a standing profession. Part 1: epidemiology. Dermatology. 1997;194(2):111-20.